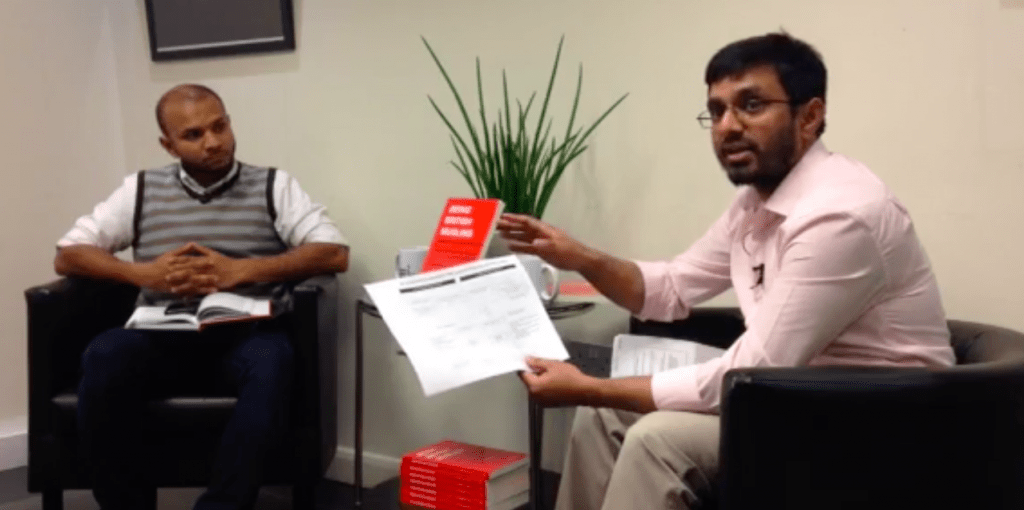

Ahmed Uddin (a senior manager at IHRC and a consultant in the development/humanitarian sector) chaired the author evening with Dr Mamnun Khan for his book Being British Muslims: Beyond Ethnocentric Religion and Identity Politics on Thursday, 21 November 2019.

Being British Muslims is available to purchase from the IHRC Bookshop here.

Dr Mamnun Khan provided a presentation to explain the main themes of the book, which he recognises as an important book for third generation Muslims especially. In the last few years, 50% of the Muslim population in the UK, were born in the UK, and Khan proposes that we do not have the experience of living somewhere else and therefore, it presents opportunities to be creative and create a new culture for ourselves.

On explaining what the book is about, Khan explains: “If you look at the situation Muslims face in the UK, there are 4 areas which Muslims are having to live in, I call them ‘pervasive headwings’.

The first is the area of the negative portrayal of Islam and Muslims in the UK. In 2002 there were less than 300 news articles talking about Muslims, and it has increased since then. 80% of these stories are negative so this trend has been there for a while.

The second is pervasive headwing is regarding the UK’s secular society where only around 11% of the population values religion as something important. The UK society is generally not interested in religion, and it is important to distinguish this from Islamophobia. Some people are negative towards religion not because of ‘hate’, but because of the dislike towards religion generally. The UK are generally socially liberal as well, so we have different values, such as marriage and segregation.

The third is on the intergenerational shifts happening; Muslims are at the bottom of socioeconomic metrics.

The fourth is what the book tries to deal with about unresolved contentions. As Muslims, our grandparents and parents came from different parts of the world and brought with them a form of Islam, a form that is appropriate for the countries they came from.”

Khan goes on to further explain that the book tries to look at such contentions and explores how to deal with it in different ways. The book does not offer solutions but presents how think about the contentions in order to move forward. Khan presented the outline of his book through a flow chart which essentially asks the question: what does it mean to make Islam relevant in the UK?

As an example, Khan says, “around 10 to 15 years ago, we would have called ourselves ‘British Arab Muslim’ or ‘British Bangladeshi’ – this would be our identity. The state would also recognise us in this way. Nowadays, our identity has become ‘British Muslim’ – how have we gone from an ethnicised identity to a faith-based identity? If we do call ourselves Muslims, then we have to ask, where is God in this picture? Are we confidently able to call ourselves Muslims and portray what faith is telling us? The book says we have jumped the gun a bit – we are calling ourselves British Muslims without really knowing what a Muslim is for our context. We haven’t contextualised Islam to the UK.” In another example, Khan demonstrates, “In applying the shariah, there is nothing in our divine writ that tells us how to deal with the crumbling NHS. So how do we deal with it? The values of healing the sick [in Islam] does exist through communal contribution. This contribution also comes with a sense of civic responsibility that disparages waste and excessive request, excessive medication. For us this is the essence of responsible citizenship towards the NHS where our morality affords all citizens access to healthcare, but that access is tempered by the social responsibility to not abuse those services. So, we call ourselves British Muslims without thinking about what it really stands for. This example shows how we need to make faith relevant to our context in the UK.”

Ahmed Uddin brought about the question of zakat funds being distributed in the UK: “I was fortunate enough to be in a discussion with some scholars specialising in zakat and one of the questions they had to answer was, should zakat be distributed locally or internationally? The three scholars unanimously said that according to their sources, zakat has to be localised. There might be the exception where the funds are needed abroad when the local need is addressed. I was thinking to myself that for the 30 to 40 years that we have been collected zakat in an organised fashion and distributing it worldwide, why on earth has it taken this long for scholarship to come out and mention something is so rooted in the scripture, that says zakat should localised? For legitimate reasons, sometimes not so excusable, there is this cowardice of scholarship to speak up and say what is right and wrong because of the fear of disturbing this balance of their status quo – an ethno-religious status quo – that they are having to work in.”

Dr Khan responded by saying that zakat changes with context massively. “You can argue that we did not have the institutional structures that have come about more recently like the National Zakat Foundation, so distributing zakat is much easier now in comparison to 20 years ago. There dispensations for when zakat needs to go further afield to keep family ties, but the reason I say context has changed now is because third generation immigrants have lost their connection to Bangladesh, Pakistan, etc. [We do not] share the same experiences or you no longer have the close relations to give zakat. Within our UK context, there are more Muslims visibly in need. Currently, approximately 95% of zakat money goes abroad and only 5% is distributed in the UK, so this needs to be shifted to perhaps 70% spent in the UK and 30% spent abroad.”

Ahmed asked Khan on the question of who has the capacity to do this. Ahmed read a passage from Dr Khan’s book which highlights acknowledging what one can and cannot manage and leaving certain things to experts. Dr Khan expands on this point by discussing that Islam teaches lean problem solving. It could be to do with individual problems like family issues as well as state issues like the tyranny of the Pharaoh, but Islam does teach ‘lean problem solving’.

Based on the Q&A with the audience, Dr Khan discussed if being British Muslim is more about an ethnicity than religion, why the British Muslim community is fragmented among ethnicity lines, the practical responsibility of contextualising Islam to the UK, how to ‘be’ Muslim and questioning to what extent are we informed by our faith in our living.