Summary of judgment in Campaign Against Antisemitism v DPP [2019] EWHC 9 (Admin), 4 February 2019 by Adam Majeed

Adam Majeed is a legal journalist based in Hong Kong

In a democratic society, freedom of expression—particularly the freedom of political expression—enjoys a privileged status in the hierarchy of norms. In this case the Queen’s Bench Division of the High Court has confirmed the high bar in place to supplant such expression and the importance in balancing free expression with the threat to public disorder and the right of others not to be harassed. The case also highlights the confidence the judiciary places in the decisions of the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) in matters of fact and the court’s role in presiding over matters of law.

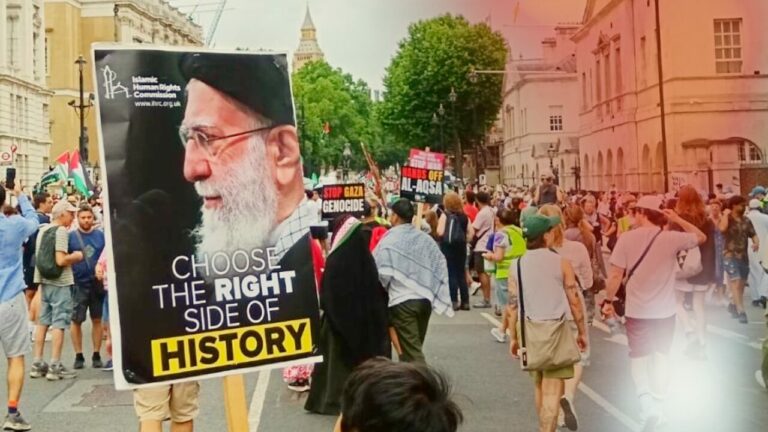

In the Campaign Against Antisemitism v DPP [2019] EWHC 9 (Admin) the context concerned comments that were made by Nazim Hussain Ali on 18 June 2017 at the annual Al Quds Day parade—a pro-Palestinian day of protest—which occurred four days after the Grenfell Tower fire resulted in 72 deaths. On 19 July 2017, Campaign Against Antisemitism (CAA) complained to the Metropolitan Police about specific statements made by Mr Ali at the rally, and on 11 December 2017 after consideration the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) determined that there was insufficient evidence for a successful prosecution against Mr Ali and decided not to bring any charges.

Consequently, the CAA decided to launch a private prosecution against Mr Ali claiming that he had acted contrary to section 5 of the Public Order Act 1986, which sanctions an individual for using threatening or abusive words or behaviour, or disorderly behaviour, within the hearing or sight of a person likely to cause harassment, alarm or distress thereby. After initial proceedings and disclosures a trial date was set for 9 July 2018, but two weeks before trial, Christian Wheeliker—Senior Crown Prosecutor of CPS London South—informed the CAA that the prosecution was being taken over by the DPP and discontinued pursuant to section 6(2) of the Prosecution of Offences Act 1985. Section 10(1) of the same Act requires the DPP to issue guidance in the form of a Code for Prosecutors, and the ensuing Code lays down a test that comprises of two stages: the evidential stage, and the public interest stage. Moreover, the Code is supplemented by the CPS Policy on Private Prosecution which states that a private prosecution should be taken over if either of the two aforementioned stages are not met. In this instance, the decision to discontinue the prosecution relied upon only one ground; namely, that the evidential stage of the Full Code test was not met.

Following a pre-action protocol letter that was sent to the CPS, the CAA claimed for judicial review on 15 August 2018 arguing that the decision maker’s conclusion that Mr Ali’s remarks were not “abusive” in the context of section 5 was irrational, and this brings us to the case at hand presided over by Lord Justice Hickinbottom and Mr Justice Nicol of the High Court.

The crux of the CAA’s prosecution rested on several specific statements made by Mr Ali at the rally that fell into three categories: those accusing Zionists for the murder of Grenfell’s deceased; those accusing Rabbis on the Board of Deputies of having “blood on their hands” and agreeing with the killing of British soldiers; and those referring to Zionists and Israelis as “terrorists”, “murderers” and “baby killers”.

Delivering the judgment, Hickinbottom LJ laid down the law, the facts, and deliberated on each of the CAA’s accusations before dismissing the claim with Nicol J in full agreement. He highlighted the importance of Article 10 enshrining freedom of expression in the European Convention of Human Rights, acknowledging that section 5 of the 1986 Act had to be read in its context with its exceptions narrowly construed (Reynolds v Times Newspapers Limited [1999] UKHL 45; [2001] 2 AC 127 and Sunday Times v United Kingdom (1979) 2 EHRR 245; (1979) ECHR 1). In addressing the law on prosecutorial decisions, Hickinbottom LJ reaffirmed that judicial review was only available if the decision-maker didn’t follow relevant lawful policy or if the decision was irrational meaning that it was “a decision not reasonably open to the decision maker on the available material”. If the decision-maker was to inform himself properly then challenges to prosecutorial decisions would succeed very rarely: see R (Monica) v Director of Public Prosecutions [2018] EWHC 3508 and R (L) v Director of Public Prosecutions [2013] EWHC 1752. Furthermore, the court reaffirmed that it was more willing to overturn issues of law and not fact since the “decision-maker’s experience and expertise in considering how that evidence will be received at trial and predicting the verdict at trial will be a particularly powerful factor”.

In addressing each of the three categories of the CAA’s accusations in turn, Hickinbottom LJ stressed that the context in which the words were said was of first importance, and that this case was clearly distinguishable from Abdul v Director of Public Prosecutions [2011] EWHC 247 as the words used in that case against homecoming British soldiers were undoubtedly inflammatory and as a result of their use a very real threat to public order, whereas in the present case there was no suggestion that there was a real risk of public disorder. Concerning the Al Quds Day parade he states:

I understand that it has been an annual event for nearly 40 years, and it generally passes off peacefully although not without a counter-protest. It is clear from the transcript that, at the 2017 rally with which this claim is concerned, there were counter-protestors from both pro-Israel and other groups, who engaged in counter-chanting. At least one individual made a succession of offensive remarks to those in the rally, repeatedly shouting and suggesting that they were paedophiles (pages 59-60). The last several pages of the transcript comprise almost exclusively counter-protestors chanting slogans including “Terrorists off our streets” and “Shame, shame, shame on you”. However, despite the opposing groups on the street at the time of the rally, there was no suggestion that there was in fact any risk of public disorder.

Having highlighted the importance of context, Hickinbottom LJ stressed the risk of decontextualising specific statements made by Mr Ali. He upheld the DPP’s assessment on the Grenfell murder accusation that the relevant remarks did not import a deliberate and direct intention on the part of Zionists to murder people in high-rise blocks, but rather that the Conservative Party are responsible for the deaths due to their austerity policies and that to the extent Zionists fund and support the Conservative Party they share such responsibility. Similarly, the accusation against the Rabbis on the Board of Deputies was construed as meaning that they do not do enough to condemn disproportionate acts of violence against Palestinians by Israel, and the claim that they agree with the killing of British soldiers was a reference to the bombing of the King David Hotel in 1946. Finally, the baby killer accusation was one that was not raised by the CAA in their prosecution but only relied upon in the present claim.

So the High Court held that Mr Ali’s comments could not be said to be abusive nor constitute any threat to public order. Mr Ali’s remarks according to the DPP “were possibly at the limits of strident political discourse [but] they were nevertheless an expression of views that he was free to hold in a free and democratic society” and the High Court agreed that such a view was not irrational.

Sam Grodzinski QC acted for the claimant and John McGuinness QC acted for the respondent in this claim before the Queen’s Bench Division on 18 December 2018.