Sandew Hira, author, economist and coordinator of the Decolonial International Network, reviews the latest book in the Muslim Experiences of Hatred and Hostility series.

“Muslims played a role in the establishment of the United States from its earliest stages,” argue Saied R. Ameli and Saeed A. Khan in their latest book “What’s Going on Here? US experiences of Islamophobia between Obama and Trump” (IHRC, London 2020). Their book is a good example of how to decolonize the history of the USA. The immediately kick in with a statement that is shocking for many colonizied historians: “The history of Islam in America predates the establishment of the country by nearly 800 years. There is now scholarly evidence that Muslim explorers found the Americas during the reign of Abd Ar-Rahman III of Cordoba in the early to mid 10th century.” (p. 8) Ivan van Sirtema, a Afro-American/Guyanese historian published in 1976 “They Came Before Columbus” documented this argument, but was vehemently attacked by white historians. Ameli and Saeed might get a similar response from the colonial historians. They give a short introduction into the history of Muslims in the USA. But the focus of the book is on the position of Muslims today in America. The authors take a comprehensive approach. They position the attitude of the American government towards Muslims both from an international and a domestic view. Their support for dictatorships like the one in Saudi Arabia goes hand in hand with their struggle against anti-imperialist forces in the Muslim world and determine to a large extent how they view Muslims in the USA.

They take a approach that combines an analysis of both islamophobia and the struggle against it. A typical example is the case of Keith Ellison from Minnesota. The first Muslim to be elected to the United States Congress he took his oath of office holding the Qur’an of American founding father and third President Thomas Jefferson. Ellison is a African-American and part of a historical tradition of Muslims who were kidnapped in Africa and transported to the America. An estimated 20% of the enslaved Africans were Muslims. Conservative whites accused Ellison for being a stealth Islamist who planned to implement sharia law once seated in Congress. They contended that Ellison’s oath was invalid as the Qur’an was not the Bible and thus voidable and meaningless declaration.

The authors point to a peculiar American feature of the history of Islam in the USA: the relationship between an existing community of Muslims that have develop an ideology and practice rooted in the struggle against racism and a group of newcomers, especially since the sixties of the 20th century. Ameli and Saeed: “Much of this dissonance was the product of skepticism about the authenticity of the Islam practiced by African American Muslims, especially those belonging to the Nation of Islam. Given the heavy emphasis on racial identity as well as the political impetus of the Nation’s black nationalism, immigrant Muslims felt estranged from the ability to achieve a common; language’ of engagement.” (p. 44).

The authors devote a whole chapter to Islamophobia and racism in Chicago and Detroit. Detroit is the city where the W.D. Fard founded the Nation of Islam. After his mysterious disappearance Elijah Muhammad relocated the ministry to Chicago where it gained national prominence due to work of Malcolm X and high profiled member Muhammad Ali. The Muslim community of Chicago counts 400.000 members, among them many Palestinians. The community has to endure systematic harassment from the government: wire taps, infiltration of mosques by the FBI, intensive surveillance, regular interviews at home by FBI agents; they all create a climate to suffocate religious freedom and create the space of violent Islamophobic attacks. It spills over to those who show solidarity with Muslims. The author cite the example of Larycia Hawkins, a Christian and the first African American woman to receive tenure at Wheaton College, a small Evangelical institution located about 30 minutes from downtown Chicago. In December 2015 she announced on Facebook that she would be wearing the hijab on campus to show her solidarity with Muslim women with a hijab who became a visible target for discrimination, bigotry and potential harassment and violence. The college administrators reacted by placing her on leave and then subsequently terminating her employment, despite her tenured status. The college was receiving considerable backlash and criticism from its alumni, some of whom were prolific and significant donors to Wheaton’s endowment. They threatened to withhold further donations unless and until the college took action against what they perceived was an unacceptable gesture toward Islam and Muslims.

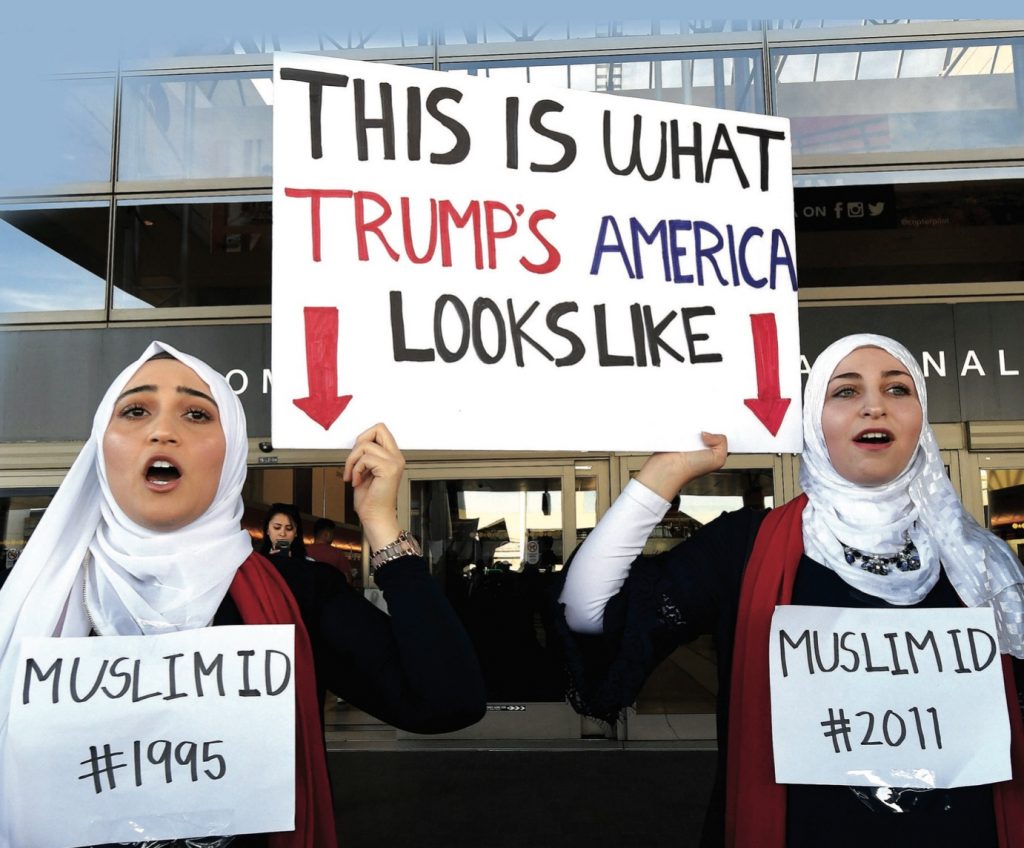

The book contains of these illustrative cases of how Muslims live in America and how the endure racism and Islamophobia. And they are put in a theoretical context. The authors use the concept of “hare crime”: “Hate crimes against individuals and groups include a wide range of criminal behaviors, including discrimination, intimidation, harassment, sabotage, assault, and murder, which vary in their severity and impact on society. These types of crimes have a common foundation in hatred. Moreover, the tendency to violence in these types of crimes is greater than in other crimes.” (p. 93). They continue: “Hate crimes against Muslims in the United States can be explained by the concept of racialization… Despite the racial heterogeneity of the American Muslim population, Muslims in the United States are defined by race. This means that they are identified as a potential threat based on racial characteristics. This racial identity is the process by which Muslims are identified and labeled through racial differences, such as skin color, as well as through culturally understood characteristics of Islamic symbols, such as beards or headscarves. While being a Muslim is not inherently related to a single race, Muslims are examined through racial characteristics that are characterized by physical aspects.“(p. 94).

With this conceptual framework they have conducted a survey on the Muslim experiences of hatred, hostility and discrimination in the USA since 2019. The survey is based on 334 interviews. It shows the pervasive nature of Islamophobia in the USA. It details the daily experience of Muslims with hatred yet there is also a note of hope. Muslims remain very optimistic that attitudes toward them and Islam would improve if people had greater personal contact with Muslims. The authors conclude: “Interpersonal contact is the most effective antidote to negative imagery and rhetoric about Muslims… At the same time, Muslim Americans should not be addled with the burden of persuading people to find them to be human. That is a self-evident reality. Rather, there need to be mechanisms that facilitate proving or reminding others of the obvious.” (p. 146)

These authors have produced a concise report on the Muslim experience in the USA with many interesting facts and a thorough analysis of how to analyze this experience.

What’s Going on Here? US Experiences of Islamophobia between Obama and Trump is published on 30 June 2020. To pre-order a paperback or digital copy please visit the IHRC Shop website here. For trade orders please email shop[AT]ihrc.org.