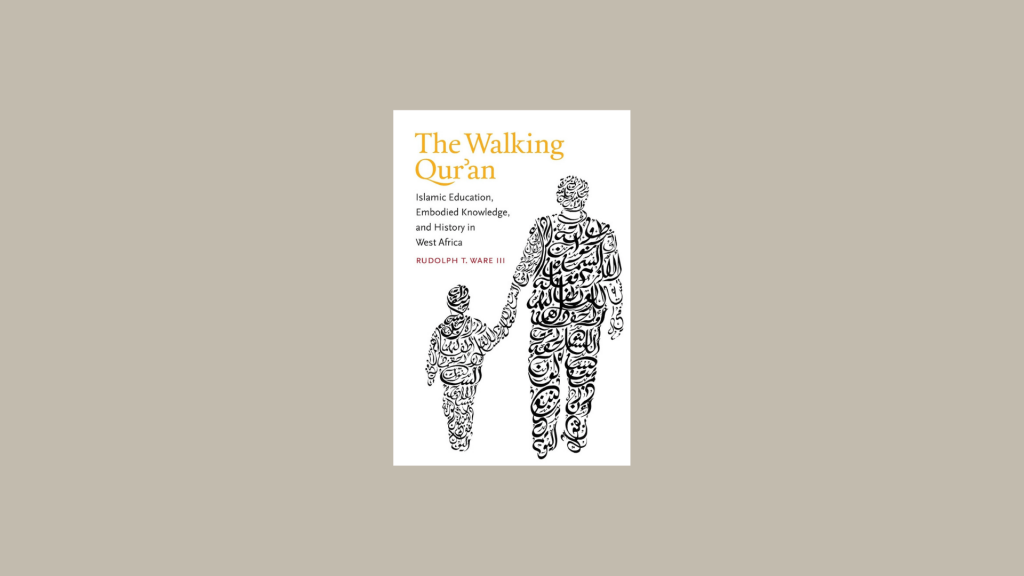

On 21 December 2021, IHRC hosted and author evening with Dr Bilal “Butch” Ware on his book The Walking Qur’an. Purchase The Walking Qur’an from the IHRC Bookshop.

WATCH THE FULL EVENT HERE:

The event was moderated by Talha Ahsan, the host of the Abbasid history podcast which is sponsored by the IHRC Bookshop. Talha introduced Dr Ware to discuss his book The Walking Qur’an, which was followed Dr Ware reading an excerpt. Please read below for some of the discussion points.

Talha: Your approach to the history of the region, you define against, what you call generously, describe as Wahabbi epistemology of Islam, you also describe that as one coin of the same….

Dr Ware: Yes, what I usually describe as post enlightenment European rationalism. So, the basic argument of the book can be deduced from the title, it can even be deduced from the cover, which shows an adult comprised of Arabic text with a child comprised of Arabic text as though the written Qur’an is flowing in to a child. It is one of those cases where a picture really is a thousand words. The thousand words, we’ll try to summarise them more briefly than that, is that traditional Islamic education in West Africa defies contemporary Islamic understandings because its not about discursive transmission of analytical knowledge, rather it’s about crafting the living breathing children of Adam into exemplars of Islam’s holy text the same way the prophet Muhammad (SAW) was described by Aisha (RA) as the Qur’an walking upon the earth.

I used the history of embodiment in Qur’an schooling not just to tell the story of Qur’an schooling, but actually as a window through which describe a number of societal phenomena. The Walking Qur’an book is an unusual book. In its first year of publication, three academic journals formed special issues just for the reviews of this book because it’s different, it hits different, like when we say it back home. The reason is because its not a description of African Islamic Epistemology that can be rightly situated as you did amongst post-enlightenment rationalist thought or its foul covered, cousin, Najdi thought, Wahabbi thought. Rather, it is written from inside this African Islamic epistemology. Its not a description, its not a translation.

What I find imperialist about most anthropology is that it essentially uses researchers to collect local understandings and translated those in in the language that white people can understand so that we can give good, informed reports. And we know anthropology is the handmaiden of colonialism. Anthropology begins when experts allow people to better dominate them and govern and colonise societies. So my ethical and moral choice in the writing of The Walking Qur’an was that I was not going to do that. I was no5 going to describe how this epistemology works and then translate it in a way that white people would understand. I was going to write a history that was inside of this epistemology that would make sense as an intellectual act, as a speech act. The book has to make sense within African Islamic understanding.

Talha: When did the people of that region realise they were Muslims?

Dr Ware: That’s a good point. The understanding is the submission to God, so it’s a discovery of something that’s already inside the human being. The answer to your question can be found in the second chapter. I’ll give the short answer here; in contradistinction to how Islam spread in West Africa, to the so-called heartlands., no military conquest carries Islam to Sub-Saharan Africa. What I often say, it’s not the Jihad of the sword but the Jihad of the wooden board that spread Islam in West Africa. There are a couple of reasons for this. The first is that in 652CE, Arab armies tried to extend their conquest of Egypt, and they are defeated by a Christian Nubian kingdom. They signed a mutual non-aggression pact so there being no conquest from Arabia to the Nile. Some later Muslims tried to contend that there were some North African armies that crossed the Sahara and made conquest of Sub-Saharan Africa, but I [found that] that never actually happened for basic reasons. The Arab geographers that wrote about the empires in West Africa before they accepted Islam, for example, historian Adh-Dhahabi. Nobody forces Islam upon West Africans. Instead those trade routes that are renewed with West Africa and North Africa lead the first merchants and then scholars to travel across the desert and ultimately the first indigenous West African merchants accept Islam. Then very, very quickly, a West African clerical class emerges and they are responsible for teaching Islam to their people. So, this was teaching that spread the religion, not politics

Talha: We often think of the peripheries as exactly that, peripheral, belie these notions of scholarly networks and sort of trade networks. And we know, for example, the rise of the Maturidi school, conversion to these Turkic tribes in Central Asia, who have come to rule the Muslim world affectively, it’s perilous.

Dr Ware: Its disastrous. Frankly, the centre-periphery models that we have, essentially foists upon us an understanding that real Islam, pure Islam is established in the centre, and that it spreads from there to other places where cultural adaptation takes place in various forms, synchronistic forms of Islam emerge, and in that narrative it is impossible to suggest that a study of Islamic knowledge in that periphery can tell you something that you don’t already know about the Islam in the centre. The argument in The Walking Qur’an is exactly that, by studying the epistemology, you actually recover an approach to knowing that used to exist at the centre and no longer does. That the memorisation of the Qur’an on wooden tablets. The literal physical ingestion of the Qur’anic text, licking it off the slate board, washing it with water, drinking that water, these are practices that you find in West Africa, and when I saw these practices, I first of all never heard of such things. In the so-called Islamic heartlands you do not find documents in association with schooling there.

I confess, I thought this was the shirkiest thing that I’d ever seen and that this had to be Africans treating the Qur’an as some kind of African fetish. And through the research for the book, once I studied the epistemological mooring of traditional Islamic schooling, I went back to the earliest Maliki teaching text that you could find in North Africa. One is a teacher’s training manual and another is written a century and a half later, and in both of these texts, they provide narrations about how in their times there’s actually a narrative that goes through the generations of tabi’un that says that “the sign of the man worthy of the name, at the time of the Khulafa Rashidun, is that you would find them with ink on their lips from licking the revelation off the tablets”.

Talha opened up questions from the audience and issues discussed were related to Islam, racism, slavery, colonialism and knowledge production. This event and this book will be of interest to those interested in Islam, racism and African history.