“The conquest of the earth, which mostly means the taking it away from those who have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves, is not a pretty thing when you look into it too much.”

– Joseph Conrad1

“ A people which is content with its homeland and which dreads even the shadow of a conflict lacks the characteristics of a superior race.”

– King Leopold II2

It is a sign of the regret and the remorse of a nation for it to apologise to its victims for past crimes committed and try to compensate them in some way. To attempt to rewrite history to conceal those crimes only compounds those injustices and functions as a continuation of that oppression. Yet, this is precisely the situation in today’s Belgium where King Leopold II’s systematic genocide of the Congolese people in the late 19th and early 20th Century is barely mentioned, whilst the king, through statues and monuments, is commemorated as a hero, the civilizer and the benefactor of the Congo.

It is obligatory on those who are truly committed to the causes of justice and human rights to ensure that atrocities such as the Belgian Congo genocide are not forgotten and remain alive in the consciousness of the human mind so that such crimes against humanity are not repeated and that those responsible are not unjustly hailed as heroes but rightly criminalised as they should be.

King Leopold II

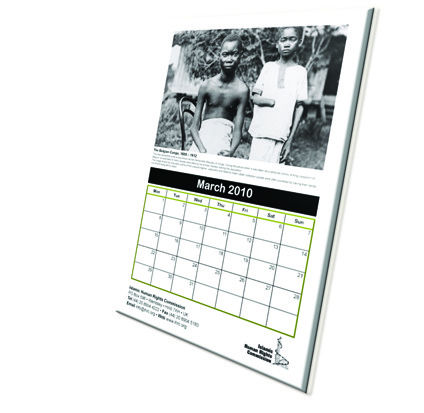

Congo’s tragic history can be traced back to 1876 when King Leopold II of Belgium sponsored an international geographical conference in Brussels where he proposed the establishment of an international benevolent committee for the “propagation of civilisation among the peoples of the Congo region by means of scientific exploration, legal trade and war against the ‘Arabic’ slave traders’. To this end, Leopold established the Association Internationale Africaine (International African Association), ostensibly an international scientific and philanthropic association but in reality, a private holding company owned by Leopold. In 1878, Leopold set up the Comité d’Études du Haut Congo (CEHC), an international commercial, scientific and humanitarian committee whose primary function was to endeavour to establish Belgian influence and sovereignty in the Congo and monopolize the rubber and ivory trade.

In 1879, under the auspices of the holding company, Leopold hired the famous explorer Henry Morton Stanley to further explore the Congo. Stanley’s real mission however was to establish Belgian sovereignty and monopoly control over the Congo rubber and ivory trade and effectively create a colony in Congo.3 Leopold’s true intentions can be assessed from a letter he wrote to his ambassador in London in which he stated, “I do not want to miss a good chance of getting us a slice of this magnificent African cake.”4

Over the course of two journeys, Stanley purchased as much ivory as he could and founded a number of settlements. Most importantly, he signed over 450 treaties on behalf of Leopold with chiefs who knowingly or otherwise agreed to give up sovereignty over their land in exchange for bolts of cloth and trinkets. Leopold asked that the treaties be as ‘brief as possible and in a couple of articles must grant us everything.’ 5 The chiefs thought that they were signing friendship treaties; in fact, they were selling their land. Leopold had studied colonial precedents used in the exploitaiton of the Native Americans and the Indians and had understood that he could show these ostensible contracts if his authority was ever challenged in future.

In 1882, the CEHC was reorganised as the Association Internationale du Congo (AIC – International Association of the Congo), a single-shareholder development company wholly owned by Leopold, who now began to push for the territory covered by Stanley’s treaties to be recognised by the international community as a sovereign state. With the sheaf of treaties Stanley had acquired firmly in hand, King Leopold embarked on a worldwide lobbying campaign to win diplomatic recognition of his new colony.

In 1884 the Conference of Berlin convened for the purpose of finalizing the colonial partitioning of the African continent among the late 19th century imperialist states. The conference concluded in February 1885 with 2.3 million square kilometres of the Congo (76 times the size of Belgium) recognised as the État Indépendant du Congo (Congo Free State – CFS) under the personal sovereignty of Leopold. He became sole ruler of a population that Stanley had estimated at 30 million people, without constitution, without international supervision, without ever having been to the Congo, and without more than a tiny handful of his new subjects having heard of him.

Reign of Terror

Under the terms of the General Act of Berlin, Leopold promised to suppress the slave trade, ‘watch over the preservation’ of the 20-30 million Congolese now subject to his rule and improve ‘their moral and material conditions of existence’. He was to also encourage missions and other philanthropic and scientific enterprises without any ‘restriction or impediment whatsoever’ and guarantee free trade. What actually happened under his auspices was one of the greatest genocides the world has witnessed, involving mass killings, maimings, rape, kidnapping and slavery, all to maximize profitability from his colonial venture.

In 1887, Leopold issued a decree declaring all land on which no European was living as ‘terres vacantes’ and therefore the property of the state. Servants of the state were encouraged to exploit such land. Next, the Free State was divided into two economic zones: the Free Trade Zone was open to entrepreneurs of any European nation, who were allowed to buy 10 and 15-year monopoly leases on anything of value: ivory from a particular district, or the rubber concession, for example. The other zone — almost two-thirds of the Congo — became the Domaine Privé: the exclusive private property of the state, which was in turn the personal property of King Léopold. Natives in the Domain Privé were required to provide state officials with set quotas of rubber and ivory at a fixed, government-mandated price and to provide 10% of their population as full-time forced labourers — slaves in all but name — and another 25% part-time.

In November 1888, Leopold issued three further decrees. The first prohibited trade in arms. The second mandated the terms for the employment of indigenous workers, and the third established the Force Publique (FP), an army created to enforce the rubber quotas through a campaign of terror. The FP’s officer corps was comprised entirely of whites—Belgian regular soldiers and mercenaries from other countries. On arriving in the CFS, these officers recruited men from neighboring non-Congolese ethnic groups—many came from warrior tribes in the Upper Congo. The FP’s primary role was to enforce Leopold’s exploitive economic policies in the newly established CFS. Armed with modern weapons and the chicotte — a bull whip made of hippopotamus hide — the FP routinely took and tortured hostages, flogged, and raped the natives. They also burned recalcitrant villages, and above all, took human hands as trophies on the orders of white officers to show that bullets had not been wasted. Each soldier was allocated a fixed number of cartridges and had to prove that they had not wasted a cartridge by bringing back the hand of the dead victim. As the genocide continued and the barbarity increased, cartridges lost or wasted through shooting monkeys had to be accounted for, so additional human hands were severed from living people to make up the necessary number.

In the words of author Peter Forbath:

“The baskets of severed hands, set down at the feet of the European post commanders, became the symbol of the Congo Free State. … The collection of hands became an end in itself. Force Publique soldiers brought them to the stations in place of rubber; they even went out to harvest them instead of rubber… They became a sort of currency. They came to be used to make up for shortfalls in rubber quotas, to replace… the people who were demanded for the forced labour gangs; and the Force Publique soldiers were paid their bonuses on the basis of how many hands they collected.“6

The Power of One

As the death toll rose in the Congo, Leopold was busy consolidating his reputation as a philanthropist and a humanitarian. Leopold claimed he was defeating the Arab slavers, as they were known, and liberating the natives from slavery. Even to this day, the Royal Army Museum in Brussels, which was built by Leopold, represents the Arab campaign as proud moment in Belgian history. The fallen Belgian soldiers are commemmorated as martyrs but there is no mention of the millions of Congolese victims of Leopold’s army.

The main witnesses to the atrocities were Christian missionaries, many of whom were reluctant to speak out against Leopold for fear of being ordered to leave the country, thereby harming their greater goal of converting the native population. Ultimately, the voice for change came from a most unlikely source. Edmund Dene Morel, a clerk in a major Liverpool shipping office and a part-time journalist, began to wonder why the ships that brought vast loads of rubber from the Congo returned full of guns and ammunition for the Force Publique. He left his job and became a full-time investigative journalist.

In 1900, he wrote a series of anonymous articles in the weekly Speaker magazine highlighting the atrocities that he discovered. He later moved to Wales and began a personal campaign against Leopold. Within six months, he had sent out 15,000 brochures and 3700 letters and eventually established his own newspaper, ‘West African Mail’ in 1903.7 Morel began gathering stories and trying to persuade missionaries to speak out about the genocide. The campaign gained momentum and Morel and his supporters persuaded the House of Commons to pass a resolution calling on the British government to conduct an inquiry into the alleged violations of the Berlin Agreement. Around the same period, Joseph Conrad’s novel Heart of Darkness was released: based on his brief experience as a steamer captain on the Congo ten years before, it encapsulated the public’s growing concerns about what was happening in the Congo.

The British consul in the Congo, Roger Casement, was sent to investigate. Casement gathered testimonies from missionaries who had witnessed first hand the atrocities and persuaded them to speak out. In 1904, Casement delivered a long, detailed eye-witness report which was made public and confirmed Morel’s accusations. The report had a considerable impact on public opinion. Casement also convinced Morel to establish an organisation for dealing specifically with the Congo question, the Congo Reform Association. Branches of the Congo Reform Association were established throughout the UK and as far away as the United States.

A war of words ensued with Leopold attempting to provide an alternative narrative to what was occurring in the CFS. Leopold commissioned books, bribed journalists, and established propaganda offices in Brussels, Frankfurt and America. He published a monthly magazine that was circulated around Europe in three different languages which was entitled, La Verite sur le Congo (The Truth about Congo)8 .

International pressure grew on Leopold and the Belgian Parliament, pushed by socialist leader Emile Vandervelde and other critics of the king’s Congolese policy, forced Leopold to set up an independent commission of enquiry. Despite Leopold’s best efforts to control the commission’s members and findings, in 1905 it confirmed Casement’s report and findings. For the first time, Belgian intellectuals and religious leaders began to come out openly against the king.

Finally on 15 November 1908, Leopold’s reign of terror came to an end when CFS was annexed to Belgium which gave him 50 million francs as a mark of gratitude. Leopold, in the meantime, tried to ensure that his crimes would never make it into the history books. Shortly after the turnover of the colony, Hochschild writes in his book, the furnaces near Leopold’s palace burned for eight days, ‘turning most of the Congo state records to ash and smoke.’ “I will give them my Congo,” the king is reported saying, “but they have no right to know what I did there.”

Leopold died the following year and his funeral cortege was booed, so hated had he become by his subjects at the end of his reign.

Death Toll

Estimates of the total death toll vary considerably. Estimates of observers of the time, as well as modern scholars, show that the population halved during this period. According to Roger Casement’s report, this depopulation was caused mainly by four causes: indiscriminate ‘war’, starvation, reduction of births and diseases which many scholars conclude were deliberately spread by Leopold’s agents. Casement estimated the death toll at 3 million for just twelve of the twenty years of Leopold’s reign. Investigative reporter and author Peter Forbath estimated at least 5 million deaths. Adam Hochschild, estimated 10 million, while the Encyclopædia Britannica gives a total population decline of 8 million to 30 million.

Legacy

Jules Marchal, a Belgian scholar and former colonial civil servant and diplomat, estimates that Leopold drew some 220 million francs in profits from the Congo during his lifetime. Much of this money was spent on building ever grander monuments, museums and urban projects in Belgium. For this reason, he is remembered today in Belgium as the ‘Builder King’ with numerous statues of him erected in many cities. These buildings were built with the profits of the Congo, yet there appears to have been a rewriting of history with no mention being made of this tragic fact. Instead, the statues of Leopold are monuments to Belgium’s denial as the profits from Leopold’s genocide are enjoyed without guilt or shame.

Remarkably the colonial Royal Museum for Central Africa (Tervuren Museum) does not mention anything at all about the atrocities committed in the Congo Free State. The Tervuren Museum has a large collection of colonial objects but no mention of Leopold’s atrocities. Another example is to be found on the sea walk of Blankenberge, a popular coastal resort, where a monument shows a colonialist with a black child at his feet (supposedly bringing him “civilization”) without any comment.

Furthermore, a deliberate attempt is being made to prevent historians and scholars from exploring this brutal chapter in Belgian history. Professor Daniel Vangroenweghe who spent ten years researching the genocide told BBC how the surviving records of Leopold’s Congo are kept underground by the Belgian Ministry for Foreign Affairs and can only be seen but not touched. Vangroenweghe, whose book Rood Rubber, leopold II en zijn Kongo was heavily criticized when published in Belgium in 1980, also stated how notes he left in the library overnight were torn up by officials on the grounds of state security.

Conclusion

Since Leopold’s time, the Congo has continued to suffer cruel and brutal treatment through further colonialism and war, both regional and civil. Belgium has developed into a wealthy and prosperous nation through the riches it gained from Leopold’s rape of the Congo. For there to be any semblance of justice, Belgium should pay the Congo compensation for those atrocities. In the current climate whereby it continues to rewrite this dark chapter in history, this seems very unlikely.

1 J. Conrad, Heart of Darkness (1902)

2 M. Ewans, European Atrocity, African Catastrophe, Leopold II, the Congo Free State and its aftermath (London, Routledge Curzon, 2002)

3 A. Hochschild, King Leopold’s Ghost: A story of greed, terror and heroism (Mariner Books, 1999), p. 70

4 BBC Four, Storyville, Congo, White King, Red Rubber, Black Death (2003)

5 Hochschild at p. 71

6 P. Forbath, The River Congo: the discovery, exploration and exploitation of the world’s most dramatic rivers (Harper & Row, 1977) as reported in The Congo Free State Genocide available at LINK

7 BBC Four, Storyville, Congo, White King, Red Rubber, Black Death (2003)

8 ibid