This article was first published in Palestine Internationalist: Volume 3 Issue 1 in 2007.

Abstract:

Dr Pappe highlights in detail how the mantra of a two state solution has been used to legitimize and exacerbate the Israeli occupation and the oppression of the Palestinian people. He contends that for Palestine to return its pre-Zionist days, Israel should be the target of an anti-Apartheid campaign which would ultimately result in genuine peace for Jews and Arabs alike.

Zionism was born out of impulses. Some would say noble impulses, definitely natural impulses, which could be understood against the background of the period when this movement was born. Zionism emerged out of the reality of Eastern and Central Europe at the end of the 19th Century.

The first impulse was the desire to try to confront the waves of anti-Semitic persecutions and harassment – and possibly also a premonition that there was even worse to come. Zionism was thus initially a search for a safe haven where European Jews could live without fear for their lives, property and dignity.

The second impulse was influenced by the European Spring of Nations in the 19th century. The leaders of the Zionist Movement redefined Judaism as a nationality rather than only as a religion. They were not the only ones who did it; around it there were many ethnic or religious groups that also re-defined themselves as nations. When the decision was taken – for reasons which there is no time to go into here – to implement these two impulses on the soil of Palestine, where nearly a million people already lived, this response to the two impulses turned Zionism into a colonial project.

Its colonialist character became all the more pronounced after the country was conquered by the British in the First World War. As a colonial project, Zionism was not a big success story. When the British Mandate came to its end, no more than six percent of the territory of Palestine was in Jewish hands. Zionism also succeeded in bringing here only a relatively small number of Jewish immigrants. In 1948, Jews constituted no more than a third of the population of Palestine.

Therefore, as a colonial project, a project of settling and displacing another people, it was not a success story. But the problem – and the source of the Palestinian tragedy – was that the leaders of Zionism did not want only to create a colonial project, they also wanted to create a democratic state. In other words they insisted that they would have exclusive Jewish majority on much of the land, at whatever price necessary. This admixture of a wish to maintain colonialist supremacy and the insistence of constructing a democratic state still feeds the mainstream Zionist thought today. This vision formulates current political positions in Israel and appears in the platforms of all the Zionist parties, including those on the left such as Meretz (nowadays renamed Yahad, headed by Yossi Beilin) and those on the extreme right such as the National Union party. The parties and all the successive governments regarded it as a supreme national priority to safeguard the overlapping between the democratic majority and the Jewish majority. Every means is fair to ensure that there will be a Jewish majority, because without a Jewish majority, the Zionist project would have to be maintained by dictatorial means and would endanger Israel’s image in the West. For this purpose it is even permissible to expel the Palestinians from whatever part is considered to be the territory of the Jewish state.

This posture developed in the first decades of Zionist presence on the land of Palestine. It was formulated more officially and specifically towards the end of the British mandate in 1948. The end of British rule and the decision to create a Jewish state in its stead forced the Israeli leadership to decide about the fate of the Palestinians who lived within the prospective Jewish state (the leaders envisioned already in May 1947 that the Jewish state would stretch over 80 percent of historical Palestine).

On March 10, 1948, in anticipation of the final day of the mandate, May 15, the Zionist leadership decided to systematically expel all the Palestinians who lived within this 80 percent (Israel without the occupied 1967 territories). There were about a million Palestinians there and the vast majority of them were ethnically cleansed by the end of 1948.

The Palestinians who remained became second rate citizens under a strict military rule and continued policy of expulsion that did not result in their uprooting due to their steadfastness and courage. In 1967, the Israeli army occupied the remaining 20 percent of Palestine creating one state of oppression from the Sea to the River. The impulse to create a front of democracy in this one state has not died down. This is why the Israelis initiated already in 1970 a peace process that would allow them to partition the areas they had occupied in 1967 to direct and indirect rule. The Western powers and particularly the US had been drawn into this process, accepting the axiom that peace is an endless search for the size of territory that would satisfy the Israeli territorial hunger. This was indeed a unique ‘peace’ process, based on the assumption that the Zionist territorial hunger and democratic wishes can be assuaged by leaving part of Palestine – the West Bank and Gaza – out of Israeli control.

This provided the Israelis a double gain: on the one hand, the demographic balance between Jews and Palestinians was not disturbed; on the other hand, the Palestinians were imprisoned in enclaves that did not allow them to resist the Zionist project.

“Unlike many other groups in the Western World, and possibly against the historical logic of those who were the victims of a hundred years of Zionist disregard, these Palestinians surprisingly want to include, in defining the future state, a recognition of the right of the Jews living here to take part in that future. Even the Jews who came yesterday from St. Petersburg and who pray in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, even the presence of these Jews is acceptable to the Palestinians.”

However, on the ground it seemed in the late 1980s that the Palestinians were unwilling to be silent pawns on the Israeli chessboard. Their resistance gave birth to the idea of a mini Palestinian state, one that would turn the imprisoned enclaves Israel did not wish to control directly into a symbolic state without any significant meaning or rights.

But even that was unacceptable to many Israelis and therefore the final presentation of this solution was delayed until the end of the 20th century. By then, consecutive Israeli governments encouraged settlers to colonize the 1967 territories. This was so successful and brutal that by the time there was a willingness in Israel to discuss the mini-state it had to be offered on a very small part of the West Bank and could not even be suggested to be a coherent territorial unit but a number of disconnected Bantustans in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

Ironically, the more impossible on the ground became the idea of the Palestinian mini state the international support for it grew. It was presented as a ‘Two States Solution’ as if two equal outfits were on the table. This blind support for the concept of ‘A Palestinian State’ became an international mantra accepted by all the Western governments including the USA but had no potential whatsoever to bring an end to the conflict.

As it stands now, the ‘Two States Solution’ means, in the accepted jargon of the powers that be, a way of arranging some kind of separation between occupier and occupied, rather than a permanent solution which addresses the outstanding questions of the Palestine question: most important of which are the ethnic cleansing Israel committed in 1948 and the gradual dispossession and oppression of the Palestinians in the 1967 occupied territories.

In the 1990s, and since the beginning of the present century, the Two States idea has become common currency. The respectable list of its supporters finally came to include, among others, Ariel Sharon, Binyamin Netanyahu and George W. Bush.

This list of adherents should have signalled out to genuine supporters of reconciliation in Palestine to abandon the Two States formula. But even before that the facts on the ground indicated very clearly that the discourse on the Two States enables Israel to deepen and perpetuate the occupation. The official Israeli commitment for peace provided the Western governments an excuse not to criticise Israel for its criminal policies in the Occupied Territories.

Under cover of the discourse of peace, the settlements were extended, and the harassment and oppression of the Palestinians increased. So far so that the `facts on the ground’ have reduced to nothing the area intended for the Palestinians. The Zionist racist and ethnic hunger got legitimacy to extend itself into nearly half of the West Bank.

A pathetic reminder of how this process worked was the early years of the 21st century when prime minister Ariel Sharon became the main advocate of the Two States solution. This master of destruction was hailed worldwide, as well as by the Israeli peace camp, as the reincarnation of Mahatma Gandhi and his cynical move to relocate the Gaza Settlers inside Israel so that the Gaza Strip could become an easy target for a genocidal Israeli policy was greeted as a move worthy of a Nobel Peace prize.

So as long as we will all continue to talk about a two state solution in the new circumstances that developed on the ground and the new international and global balance of power in mind, Israel will be able to continue the occupation by other means, in order to silence the outside criticism of the acts of the occupation.

But it is not only the actual realities on the ground that defeat the idea of two states. One assumes that the idea of two states appeals to those who believe Palestine should be partitioned between the two nations, or ethnic groups, that live on it. This stems from the old notion of biblical justice in the west, reaffirmed by what may seem as a commonsensical approach to the problem. Seen from this perspective, there is no formula more cynical than the Two States Solution: after all it offers 80 percent of the country to the occupier, and twenty percent to the occupied. That is, 20 percent in the best and utopian case. More likely, no more than 10 percent, a dispersed and surrounded ten percent, to the occupied. Leaving aside the point that is cannot contain a reasonable and just solution to the refugee problem as they would have nowhere to return to.

On the other hand, if pragmatism and “Realpolitik” be our guiding lights, and all that we wish is to assuage the Zionist State’s territorial hunger with a demographic efficiency, why offer only 80 percent? If brute force alone is to determine the solution, there is no need today to offer the Palestinians even half a percent. And indeed a growing number of Israeli pragmatists in the Labour party suggest moving a large number of Palestinians in Israel to the enclaved Bantustans of the West Bank.

The idea has still life in it because there are West Bank Palestinians who are willing to rest content even with the smallest part of the land provided it would end the occupation. But these Palestinians and their representatives in Ramallah are only part of the Palestinian body of politics and time has come to hear the voices and visions of the Palestinians in the refugee camps, in the diasporas, in other parts of the Occupied Territories and the Palestinians in Israel. Many of them, in growing number, express a wish not to be future citizens of mini-Palestinistan, but of a future state which will include the whole of the country which was once Palestine. There will be neither reconciliation here, nor justice nor a permanent solution, if these significant sections of the Palestinian people will not have a share in solving the questions referring to reconciliation and to defining the sovereignty, the identity and the future of this country.

Unlike many other groups in the Western World, and possibly against the historical logic of those who were the victims of a hundred years of Zionist disregard, these Palestinians surprisingly want to include, in defining the future state, a recognition of the right of the Jews living here to take part in that future. Even the Jews who came yesterday from St. Petersburg and who pray in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, even the presence of these Jews is acceptable to the Palestinians.

In respect for their aspiration and voices new alternatives for peace should be discussed instead of the failing formulae of yesterday. Their call for rebuilding their homeland is not just nostalgic or utopian. It seems to take into account the present location of the various ethnic groups on the land: Jews and Palestinians live in such intertwined way that separating them meaning forced transfer and abuse of elementary rights.

It is also an idea that corresponds to the basic and most elementary principles of democracy, human and civil rights. One person, one vote: that would decide the future structures and policies of the country. A shared democracy that respects ethnic, religious and cultural diversities but does not allow any group to discriminate against the others.

The idea of partition is sixty years old. It has wrought havoc and destruction ever since its inception and the continued international advocacy for it is a recipe for more violence and oppression. A discussion on righting wrongs of the past is a more useful way forward than the ruler of the geographers. The right of the victims of the ethnic cleansing to return, of the occupied to be liberated, and the discriminated for equality. The right also of the Jews who live in Israel to share the land and the state.

The one who expelled and his sons and grandsons, and the one who was expelled with sons and grandsons and granddaughters, all of them together must take part in the negotiations on the future of the entire country.

The political elites on the ground are incompetent in the best case and corrupt in the worst, in all that pertains to finding a solution to the conflict. The elites which accompany the ‘peace process’ in the Western World and the Arab World are just as bad. When these elites masquerade as Civil Society, simply because there are some politicians who happen not to hold office at a certain moment, the Geneva bubble is floated and the situation becomes even worse and peace even further off.

Everyone should be consulted in the process, including the expellees of the past and their successive generations and those who were left after the expulsions. They should be consulted about the suitable political structure that would be able to respect the principles of justice, reconciliation and coexistence.

Finally, it is also important to divorce the concept of a future solution and the need to end the occupation. Since the two state discourse was not about peace, the world accepted the common Israeli assertion that it does not have to ease the occupation even slightly before a peace deal is struck. As the process was not about peace but at best of limiting the size of the territory under direct occupation, the process was seen rightly by many in Palestine as a gimmick at best and as a plot to destroy the Palestinian people at worst. The despair was accentuated by the false hopes that were raised under the banner of a peace that allowed the occupier to extend its colonization and destruction.

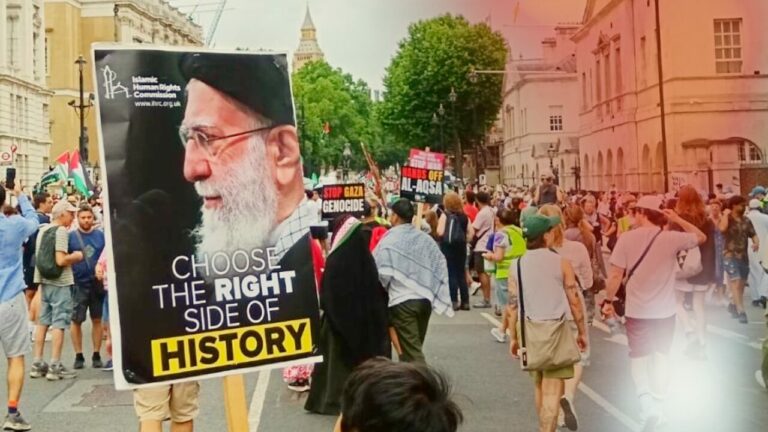

The military presence in Israel should be a target for an anti-Apartheid campaign not a peace process. Through sanctions, boycott and divestment the Israelis should be forced out of the Occupied Territories and only then invited for a comprehensive discussion on the future. Without such pressure alas the Israeli political elite would not budge and the result would be not just further destruction of Palestine, but the danger of another Middle Eastern war. Regime change by itself is not an abhorrent concept. In the case of Palestine, and for the sake of Jews and Palestinians, it should be achieved not by war and violence, but by non-violent civil action and a genuine process that would allow Palestine to return to its former pre-Zionist days: a country of hope, coexistence and peace.

Courtesy & Copyright © Palestine Internationalist

Ilan Pappe is a Professor in the Institute for Arab and Islamic Studies at the University of Exeter, Director of the European Centre for Palestine Studies in Exeter and the Co-Director of the Exeter Centre for Ethno-Political Studies. He was the academic head and founder of the Institute for Peace Studies in Givat Haviva, Israel (1992-2000) and the Chair of the Emil Touma Institute for Palestinian Studies in Haifa (2000-2008).

He is one of the “New Historians” who have critically re-examined the history of Israel and Zionism.

His latest book Out of the Frame is available now on the IHRC on-line shop.