Liberation beyond the liberal and authoritarian

Volume 2 – Issue 2 – May 2020 / Ramadan 1441

Editorial

As this editorial is being written, many in the West are several weeks into quarantine and isolation. Others, notably in China are tentatively emerging from the nightmare that the coronavirus pandemic has unleashed around the globe. This period of turmoil has brought to the fore questions of structural failure, accountability, responsibility and the future. What world will we all be emerging into once – God-willing – the pandemic eases, and eventually the virus is contained?

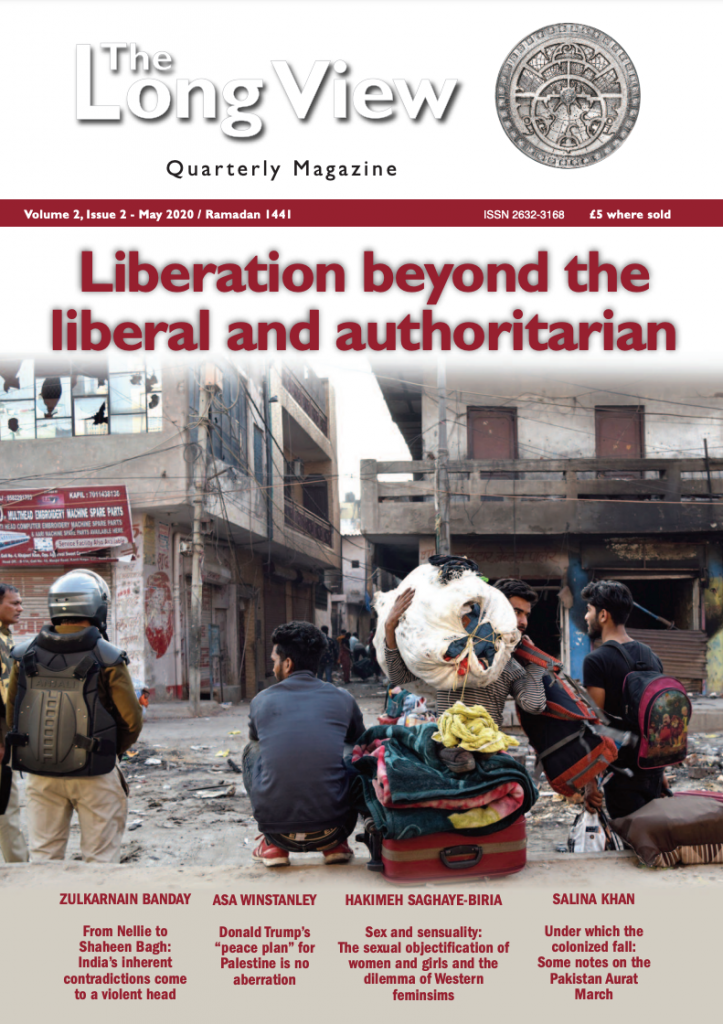

This issue’s contributions address these questions in several ways. Our main article overviews the history of the current events in India. Zulkarnain Banday argues persuasively that far from being a recent phenomenon, the anti-Muslim hatred being unleashed by the current right-wing Hindutva government finds its origins pre-independence in the RSS movement, and the failure of independent India to tackle the supremacist narratives that have seen many if not all minoritized communities faced with institutional discrimination and vigilante, paramilitary and state violence. Whether fashioned as secular, plural state or authoritarian Hindu(tva) nation, India has failed to deliver equality, citizenship and security to Indians. The modes of resistance being witnessed on the streets – before lockdown – and in civil society spaces must be where the future of India is salvaged from this cycle of violence and hatred.

Moving to Palestine, Asa Winstanley looks at the so-called deal of the century announced by Donald Trump in January this year. Whilst condemned as an exceptional move – and denounced even within some Zionist circles, the deal itself is not as controversial as first readings might suggest. Winstanley argues that successive attempts to bring ‘peace’ to the conflict, and the discourses that have supported these initiatives are themselves replete with the same prejudices, injustices and exceptionalism that have caused and perpetuate the dispossession and ethnic cleansing of Palestine. Put simply, nothing has changed, and nothing is different in this deal. It is only more crudely and violently put forth. The challenges for Palestinian resistance, solidarity and the ultimate project of liberation remain vast – the deal both exposes the failed two state solution option and makes the one free and equal state option that more difficult to express. But as Winstanley argues, the Palestinians have been through worse and they will overcome this also.

This limitation of the discourses around national being are brought into further sharp relief by the next two articles that tackle narratives of women’s empowerment. Women’s liberation movements, ideas and policies are in these submissions, sites of colonisation, depoliticization and outright oppression. In failing to give voice to ideas of liberation from non-Western thinking, such movements are simply replicating colonial forms of control under the guise of women’s freedom.

Hakimeh Saghaye-Biria and Salina Khan take the theoretical and practical policies of Western(ised) feminisms to task, both writers expressing warnings to movements for women’s liberation in the Global South. Saghaye-Biria looks to the internal critiques of feminism by women’s activists who call out the sexualization and objectification of women in Western culture. The pernicious impacts on women and girls and the effective institutionalisation of rape culture should be sounding louder alarm bells amongst feminist movements. However, when it comes to making policy and, in particular, promoting supposed egalitarianism in the South / developing / postcolonial world, this critique is little heard. Instead policies that propose an ill or more often sexually defined nature of ‘freedom’ are replicated. In so doing, these policies are not only neo-colonial but at best irrelevant for the women they are supposed to help and at worse dangerous for their welfare and the culture they replicate in their institutionalisation. Saghaye-Biria delves deep into the nexus between consumerism and the beauty industry, the money made from creating a culture of female self-loathing and the ultimate depoliticization and suppression of women as a result in Western(ised) settings.

Khan looks to the recent Aurat (Women’s) March in Pakistan. Whilst acknowledging the very recent shift in the movement towards welfare support and advice in the wake of the pandemic, she notes it is influenced by the Women’s March in the US and its wholesale adoption of slogans and ideas is not simply an ill-fit for Pakistani women but leaves them open to further abuses.

Both Khan and Saghaye-Biria look to ways that Islam has been used to reimagine liberation for women and society in the current era. Their arguments are surely part of the wide conversation that needs to be had that no longer looks to the failed binaries of political ideas from the North. In reimagining the world that we want, we need to be brave enough to look to those ideas, that have been maligned and excluded along with the people who espouse them if we really do want a new and better world to emerge. The West has been found wanting in this global crisis on an unprecedented scale. It’s time to move on.