The Need for Better Political and Emotional Spaces

Volume 2 – Issue 3 – June 2020 / Dhul Qa’dah 1441

Editorial

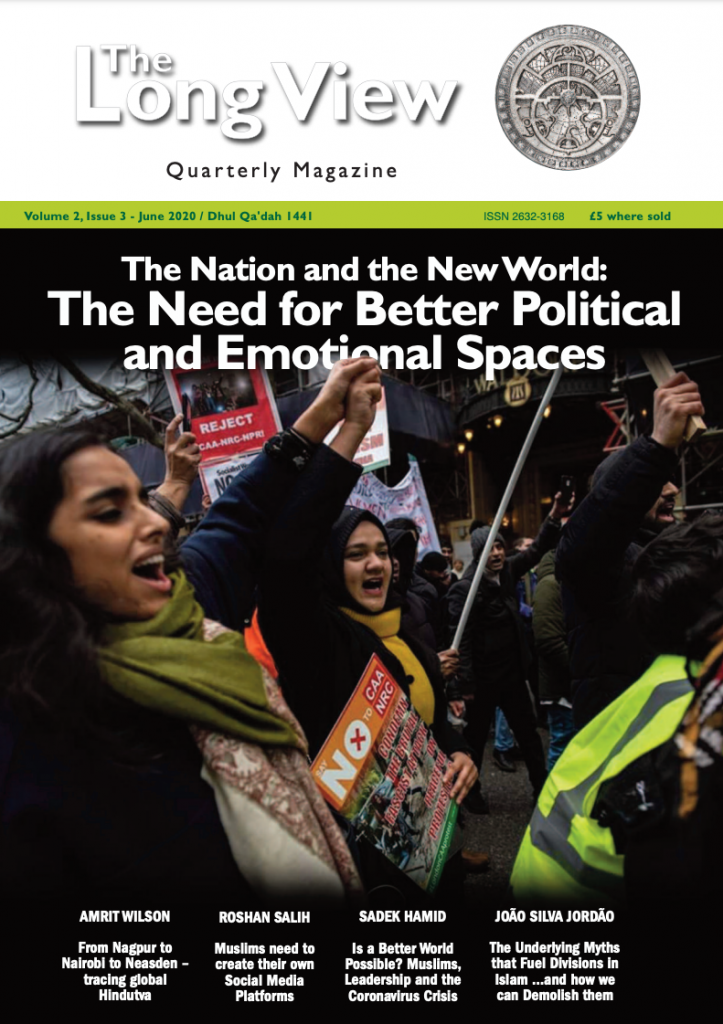

India’s problem with fascism is well documented. While many point to the 1992 demolition of the historic Babri Masjid as a seminal point in the rise of Hindutva supremacist politics, the seeds of today’s domination of the national political landscape were planted several decades before India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru hoisted the national flag above the Lahori Gate of the Red Fort in Delhi in 1947. Far less has been written about the spread of these ideas – inspired by Mussolini and Hitler – in the Indian diaspora.

Our lead article by Amrit Wilson, an expert on the Indian diaspora, locates the rise of the Hindutva movement in the UK in the racialised political systems of British colonial systems in east Africa and the subsequent socio-economic disruptions occasioned after their independence. Hindutva found a captive constituency in once successful economic migrants turned political refugees who now found themselves at the bottom of the class system in the UK.

Instead of directing their ire towards their oppressors, many Hindus found solace in the message that whatever their predicament, they still ranked above Muslims in the pecking order. From very early on, the Rashtrita Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) directed its efforts at controlling Hindu social and political organisations which sought to perpetuate caste-ist and anti-Muslim ideas both in the UK and back in the homeland.

The mainstreaming of Hindutva has made it more difficult for opponents to argue that it is a hate ideology not deserving of any kind of public platform. Social media in particular, with its notoriously loose restrictions on hate content, has been a fertile campaigning grounds for this far-right. But the increasing influence in social media companies of Zionists, anti-Muslim bedfellows of Hindutva, has made the prospect of curtailing Hindutva even harder.

In our second article, the founder of the Muslim news website 5Pillars Roshan Muhammed Salih, shares his experiences of the discrimination he and other Muslim-led organisations face to simply share content via the main social media platforms. Whether it’s over articles highlighting Israel’s continuing oppression of Palestinians, or criticism of the western liberal drive to normalise homosexuality, Facebook, Twitter and YouTube have all been very eager to censor them and sanction the originators, often with serious financial repercussions.

The social media behemoths have proved vulnerable to state influence even if it means compromising their much-lauded commitment to freedom of expression. Salih has seen his initial excitement at the space offered by digital media to challenge the anti-Muslim mainstream media give way to cynicism and a questioning of whether the US social media giants can provide Muslims a genuine platform to speak for themselves.

If the expansion of the internet has failed to break the dominance of corporations and states in controlling information content, it has also proved to be a useful tool in propagating anti-Muslim views. Among the more preposterous anti-Muslim campaigns being waged by India’s ruling BJP is the Corona-jihad, the idea that Muslims are deliberately infecting Hindus with the Covid-19 virus in pursuit of a religious war. As the pandemic rages across India, the ubiquity of social media has simply provided another opportunity to demonise Muslims In India, leading amongst other things to the scapegoating of the country’s Tabligh-Jamaat movement.

As we put this issue to bed the deadly virus shows few signs of relaxing its grip on the planet. The microscopic parasite that has paralysed the world is forcing us to rethink many of the things we take for granted. Across history, as Dr Sadek Hamid reminds us in the third article, pandemics have often led to huge social and economic upheavals. But as old orthodoxies start to be questioned, he laments the response of Muslims which he claims has been largely confined to navel gazing about religious particulars. Instead of contributing to wider debates about the environment and public health many in the community’s leadership have just been fixated on what it means for collective ritual worship.

For the author, this exceptionalising of the pandemic highlights the glaring “divide between those whose worldview clings to an imagined literalist past that denies the validity of knowledge outside scriptural sources and those that want to contextualise their religious heritage authentically to apply it to the challenges of the modern world.” The pandemic has created a climate in which everything is once again up for debate and it behoves us as the heirs of a history-changing intellectual tradition to make more meaningful contributions to the bigger universal challenges facing us as human beings.

In spite of the deathly plague sweeping the world, the Sunni/Shia schism in Islam is one of those festering wounds that continues to play out in bloody violence. Few Muslim countries have been spared the conflicts that are often political in nature but are nevertheless expressed and justified in doctrinal terms. Our final article is a personal plea from a Muslim to end this crippling impasse. João Silva Jordão proposes that we break with the personality-oriented histories which characterise discussion of leaders after the first four of the Prophet’s successors and “spiritualise” the concept of leadership to focus on the message that they each conveyed. For Jordão political legitimacy should not rest in the material fact of leading the community but in how faithfully the candidate conveyed the Prophetic message.

In focusing on message, Jordão offers a way of reimaging our world outside the ever constraining narratives that currently effect so much of the oppression experienced today. It is a sliver of much needed hope. We should heed it.