From Bosnia to the US: Fighting religious and political particularism

Volume 3 – Issue 1 – January 2021 / Jumad al-Akhirah 1442

Editorial

People get the leaders they deserve, the saying goes. This saying does at least hold true for democracies in which people have the power to choose who governs them. That the citizens of the UK and US decided in recent years to elect boorish, unextraordinary imbeciles to the highest office speaks volumes about the dumbing down of politics and the social and economic changes that have given the polarising policies of Boris Johnson and Donald Trump mass appeal.

In our lead article in this issue, Saeed A. Khan explores the reasons for rising populism in the US. He locates the breakdown of centrist politics in the US in the Reagan era when a former Hollywood heart throb ignited a smouldering Christian conservatism by framing the Cold War as a fight between God and the devil. Viewed through this lens, the collapse of communism was seen as a vindication of Christianity and conservatism. More importantly it held out the promise of a new paradigm of social engineering that has fuelled the efforts and ambitions of some Christian movements ever since. The movement has accelerated in response to a moral panic over changing demographics which point to the white majority becoming a minority by 2050 and also the challenge posed by China to the US’ global economic dominance.

Looking ahead, the incoming President Biden will start his stewardship of a nation that has deeply embedded structural flaws and vulnerabilities. His immediate priority will be to repair the damage wrought by his predecessor, which will require a huge amount of healing and reconciliation. Khan is pessimistic:

“The past four years have been marked by a normalisation and even an endorsement, explicitly or implicitly, of bigotry, racism, Islamophobia and anti-Semitism, among a list of attitudes that are antithetical to social cohesion. While the new president can certainly reset the official government tone of what will and won’t be tolerated, a recalibration of civil society may prove far more elusive, given the depth of discord and distrust among various factions in the country.”

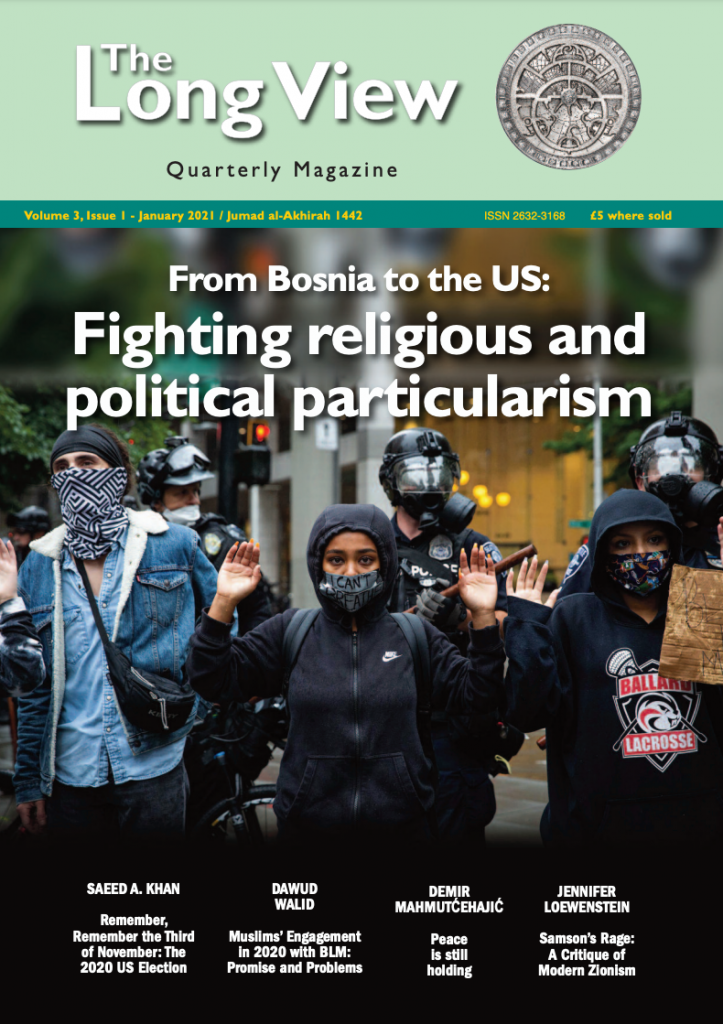

The extent of the fissures in US society have nowhere been more exposed than over the lingering issue of racism. Last summer’s murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis by a white policeman once again brought anti-racism protestors flooding onto the streets only to be met by a counter movement comprising white supremacists reacting to what they saw as a near and present threat to White Anglo Saxon hegemony. The Black Lives Matter network (BLM) soon assumed the leadership of the movement, also receiving backing from US Muslim groups after years of scepticism and wariness.

In our second article, Imam Dawud Walid argues that this standoffishness is still justified. There is a big difference between standing up for the dignity of Black life and BLM. Specifically, elements of the BLM network, particularly those championing LGBTQ+ aims, espouse values that are diametrically opposed to Islam. Moreover, the aggressive, even if non-violent, protest tactics of certain BLM activists are far detached from the Prophetic method. While welcoming the belated take-up of racial justice causes by US Muslims, Walid is concerned that the faithful remain guided by sacred principles: “It should not be the case that Muslims are completely copying BLM including using their language which seeks to normalise and promote the forbidden, nor should they be actively given platforms within our community which could further confuse our community, especially the youth.”

Moving away from the US, our third piece analyses the dangers posed by irredentism to the integrity of Bosnia Herzegovina.

The Dayton Agreement of 1995 marked the end of the regional wars that broke out following the dissolution of the former Yugoslavia between 1990-1992. As some of the autonomous regions and republics exercised their peoples’ desire to gain independence from the Serb dominated state, they were attacked and invaded by Yugoslav armed forces. The complicating factor in Bosnia was that it was also invaded by a secessionist Croatia which laid claim to territory there. By the time the Balkan wars had run their course, an estimated 140,000 people had lost their lives, some in the worst massacres to afflict mainland Europe since the Second World War.

Demir Mahmutćehajić argues that centrifugal forces based on religio-politics continue to undermine the survival of a federal Bosnia. He describes the current state of affairs as something less than peace, a ceasefire that cannot last indefinitely, especially given that the protagonists are expending great efforts to establish a legal basis for their objectives. Sooner or later, according to Mahmutćehajić, the openly expressed desire of Serbs and Croats to secede will be translated into action.

Our final piece by Jennifer Loewenstein describes how modern Zionism, informed as it is by racial exceptionalism, land theft and necessary violence, continues to blight the lives of Palestinians in their own homeland. Interspersed with accounts of their harrowing everyday ordeals which she herself has witnessed at first hand, Loewenstein highlights how the foundational principles of the country that purports to be the only democracy in the Middle East fly in the face of the most basic democratic principles and human rights.

She writes: “Try as one might to argue that Israel can be Jewish and democratic simultaneously, the history of Israel and the facts of daily life belie this claim. The mechanisms of exclusion reach far beyond empirical data. An ingrained system of belief and more than 70 years of indoctrination sponsored by state legal, educational, and military institutions will remain no matter how eloquently Israel’s apologists might hope to wish them away.”

These bleak pictures of the arguably inherent inequalities of nation states are a necessary reminder for those interested in a just future, that only a fundamental change in how we politically organise is required. The way we work as movements and networks needs to understand that, if we are to move towards a world free of the violent harms of the ideas of ‘nation’ and ‘state’ that we live today. Let’s organise.