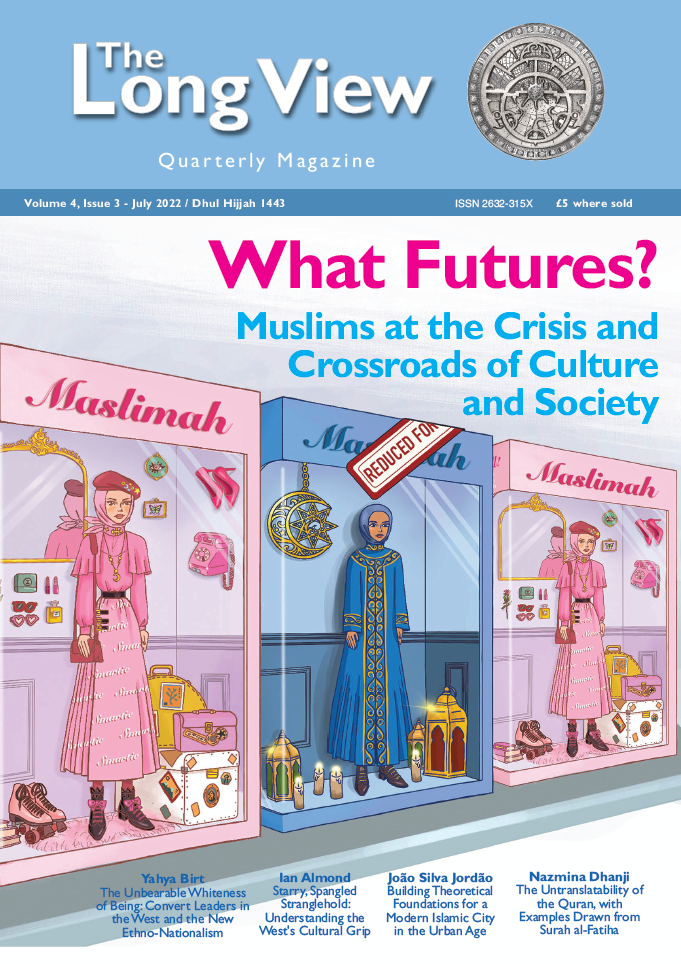

Muslims at the Crisis and Crossroads of Culture and Society

Volume 4 – Issue 3 – July 2022 / Dhul Hijjah 1443

Editorial

The nativist pushback against the two-decade old orthodoxy of multiculturalism has yielded a discourse inimical to the fight for equality of Muslims in the West. Manifested in openly Islamophobic calls for state discrimination against Muslims by the likes of the Henry Jackson Society or the apparently benign guiding hand of a sympathetic ‘liberal’ left leading us, especially our women, to integration, the discourse is now entrenched and the daily battle against it an endless drain on meagre Muslim community resources. The last thing Muslims need is for leading thinkers in their midst to contribute, albeit inadvertently, to a narrative that perpetuates and even accentuates the “problem Muslim” narrative.

Yet, according to Yahya Birt, this is exactly what white scholars like Abdul Hakim Murad and Hamza Yusuf are guilty of in advocating a place for Islam in the West that concedes too much ground to majoritarian cultural expression. Their apparent preference is for a gorafied Muslim (to use Anglo-Urdu street slang), totally denuded of his inherited cultural mores and reclothed in all the ways of his “host” society. It appears that in their view, Muslims of non-native origin have alienated their western “hosts” by clinging to their own nativist ethnocentricism. However, while there may be truth to this, according to Birt, the solution does not lie in propounding a rival ethnocentricism. There is no deculturated Islam: there is only an endless process of deculturation and re-culturation. Islam is a universal faith that includes within it all cultures, and furthermore that cultural difference is part of the Divine plan. “Therefore, when “white” converts re-culture Islam in their own terms, which is their right as members of a universal faith, they can only do so authentically if it is also anti-racist and builds solidarity with racialised Muslims,” says Birt.

The predominance of white cultural expression is a theme taken up by Professor Ian Almond in our second article. As an infant, Almond says he dreamed of escaping his dreary British childhood and escaping to California or New York or Chicago where Hollywood projected that magical things and events of tremendous significance occurred. Little was he to know then that much of the influence of the west was exercised through television and cinema by genre, a phenomenon that persists to this day. Through colonialism – at its peak in 1914, 85 percent of the planet was governed by European or European-settler countries – western powers installed and cultivated their own ethics and values creating a ready audience for their cultural productions. “The ‘aura’ surrounding Shakespeare or Paris or the Statue of Liberty is a consequence of centuries of effective and systematic self-mythologising”, not any cultural or civilisational supremacy, argues Almond. There is little prospect of this Eurocentrism weakening so long as control over the majority of the world’s economic resources remains concentrated in the West – imperialism’s most abiding legacy.

Economic and political inequality also manifests itself in the urban landscape through the design of our towns and cities. About half of the world’s population currently lives in cities, a figure that is estimated to rise to 70% by 2050. As they expand, resolving urban conflicts, poverty, inequality, segregation and suffering is increasingly becoming a key challenge for planners and policymakers. But this cannot be achieved by simply tinkering with the built environment, according to João Silva Jordão. The solutions to urban problems are both political and architectural “and it is only through reforming the political processes that permeate the city and in particular its planning and management instruments that a fairer city can be achieved.” This requires the inclusion of all its inhabitants in decision making, giving them a degree of influence over the processes and hence the environments that shape their lives. In the Muslim world the problem is compounded by the adoption of architectural philosophies that are now widely considered as having failed in the western world. Jordão emphasises the need to conceptualise “The Islamic city”, a place where the values and concepts of Islam are imbued in the very fabric of the city and through which the very essence of the philosophy of Islam takes physical urban form as well as becoming the prime arena in which the ideal Islamic society can develop.

Inequality is a theme indirectly addressed in the final article of this issue. The Quran claims to be the final revelation and directed at all people irrespective of culture and ethnicity. Yet it is written in Arabic, a language that is not native to the majority of people on the plant giving rise to an obvious question: How can a book that claims to be universal retain its claims to equality if it is written in a language that is alien to most readers? The problem of understanding the Qur’an is one that has undoubtedly confronted all non-Arabic and indeed Arabic readers of the Holy Qur’an at some point. Many commendable attempts have been made to translate it into numerous languages but all face the seemingly insurmountable problem of conveying the precise meaning of a scripture whose divine origin makes it the highest expression of eloquence. Using Surah al-Fatiha, Nazmina Dhanji demonstrates some lexical, syntactic and semantic problems that arise with translating certain words and verses. In doing so, she enriches our understanding of the opening chapter of the Holy Book, and surmises that the need to open our minds, and reconnect with our innate understandings of our creation and createdness, is in fact the process that the Qur’an demands. There can be no one reliable translation of the Qur’an in this scenario, but there can and should be a process of divesting ourselves of the limited understanding of language and culture combined. This sounds like a message we can reapply across the board. We hope this issue is a small part of that process.