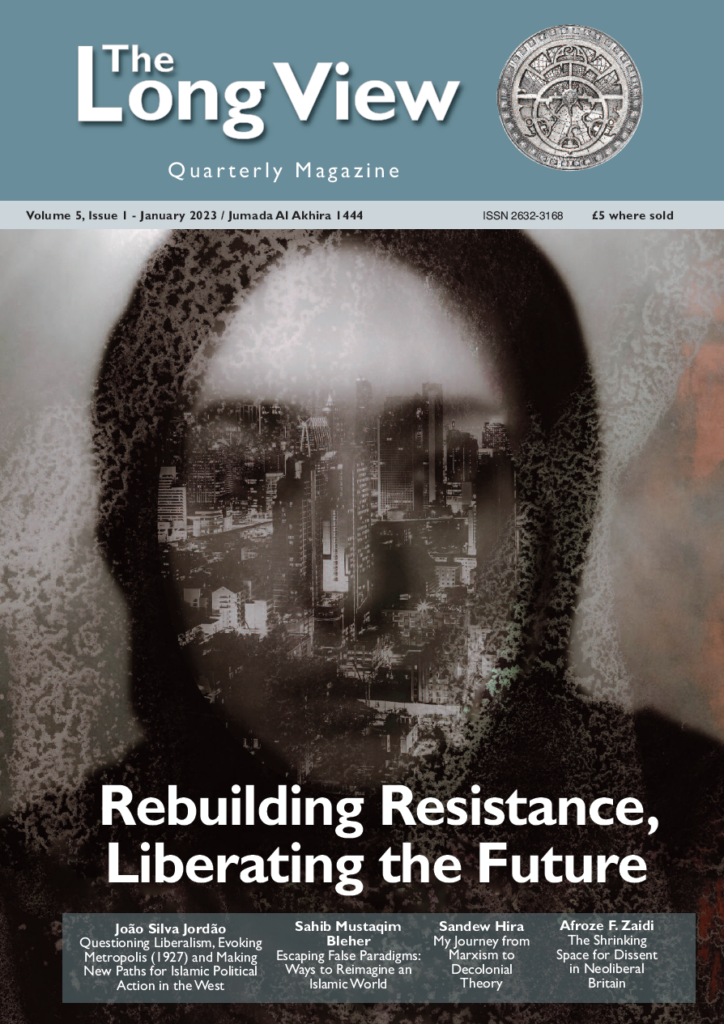

Rebuilding Resistance, Liberating the Future

Volume 5 – Issue 1 – January 2023 / Jumada Al Akhira 1444

Editorial

The push for a new world has perhaps never been stronger in the last 500 years than now. Over a century of turmoil is littered with examples of both the struggles and victories for liberatory movements, and onslaughts and regrouping after the defeat of those forces dedicated to upholding the status quo ante. What lessons can be learned from this period, and where should those of us committed to justice and transformation critique ourselves in the effort to bring permanent change?

João Silva Jordão’s essay sets out the stall for an Islamic politics in the West, one that rejects the requirement to internalise the contradictions of liberalism as a pre-requisite for participation of Muslims or other minoritized groups. This is perhaps best exemplified by the alliances between Muslims and the European left, which has exposed a fault line with regard to the expression of Islamic cultures, morals and ethics e.g. the instrumentalisation of Islamic values regarding sexuality as a stick with which various commentariat tried to beat the Qatari government during the football World Cup, or the knee jerk reactions to claims of inequality due to the wearing of hijab in Iran and elsewhere. The internalisation of such mores amongst Muslim diaspora leadership and even in some Muslim movements and governments in majority settings has become a hindrance to transformation.

This politics is not completely an act of imagination. According to Jordão the possibilities of such praxis exist already in alliances with Christian Democratic politics. It also exists deep in the cultural imagination of Europe, with Jordão highlighting the anti-fascist messaging of Fritz Lang’s classic film ‘Metropolis’. Having the courage to lead change by standing up for values that are labelled Islamic but which cut across human divides – for a freedom that is fair and just, is a theme that runs through our second essay, based on extracts from Sahib Mustaqim Bleher’s book ‘Conceptual Islam: Escaping False Paradigms’. Looking at an imminent Messianic end of times, Bleher argues that the returning Mahdi must not simply be recognised by those of us claiming to be awaiting him, but that those followers must be competent. This competence, currently lacking in Muslim organisation and at the individual level, requires us to look beyond the economic and social structures that currently exist. Reformulating these, he argues, though difficult, is the essential goal of Muslims, to bring about a world where justice for all can prevail.

As with Jordão, Bleher is cognisant of the role of the city – in this case however providing one of the barriers to a blanket self-sufficiency for individuals and small communities. Likewise economic solutions like returning to the gold standard, take us nowhere in the current age, where the vast majority of gold reserves are controlled by those in whose interests it is to continue the current economic order in all its grotesquely.

Our third essay, from Sandew Hira, is a deeply personal yet pertinent account of his ideological journey. From a young die hard Marxist inspired by the student movements and agitations of 1968 and the revolutionary fervour of the mid-20th century, he finds himself troubled by the unbending authoritarianism of thinking as well as its failure to materialise further revolutions after the Russian revolution of 1917. This journey – from member of communist movements in Holland to decolonial thinker and scholar reflects a sea change in thinking. His courage to question Marxist claims as the only alternative to capitalism and the crises caused by it, is an exemplar for young activists. Part of his journey comes through his exposure to other ways of thinking, specifically movements with religious world-views. Other parts come from the political movements and crises of Suriname from where he originally hails, and where at great cost he has tried to bring about reconciliation and compromise between factions, hitherto at war with each other.

Hira’s rejection of the sectarianism that characterised his experience in Marxist movements is reflected in the divide and rule fomented by the UK government between various sections of British society. Our fourth essay by Afroze F. Zaidi, looks at the controlling mechanisms whereby the British government has closed down political space and effectively depoliticised the masses. Having written last year about the processes of closing down dissent from Muslims, Zaidi argues that the same processes are being used against the majority population. As the UK moves painfully through a cost of living crisis, Zaidi forensically picks apart the collusion of mainstream media in creating divisions – highlighting how strikers are depicted as ruining both the annual Christmas holidays (even with exaggerated or patently false accusations), but also conditions for other (low paid) workers. This pitting against each other of sections of society mirrors all too well the way Muslims in the UK have been divided and ruled for decades by a government and compliant media and institutions, with the notions of the ‘good’ and ‘bad’ Muslim.

As with the depoliticization of Muslims through programs like Prevent which simultaneously socially engineer and scare adherents of Islam into silence or worse still a belief in an assimilationist and or assimilated Islam, wider British society now finds its politics of protest, dissent and even mild opposition criminalised (as Zaidi explains through the new policing laws), and their dissent subject to an ever shrinking media and civil society space, and indeed the work of think tanks and bodies like the Commission for Countering Extremism, that have for some time now identified left wing, environmental, trade union and other political movements as inimical to the notion of a cohesive society and British values.

There are many lessons to be learned from these essays. We hope you will continue the conversations they raise as we try and make the now palpably different future, one that liberates all of us.