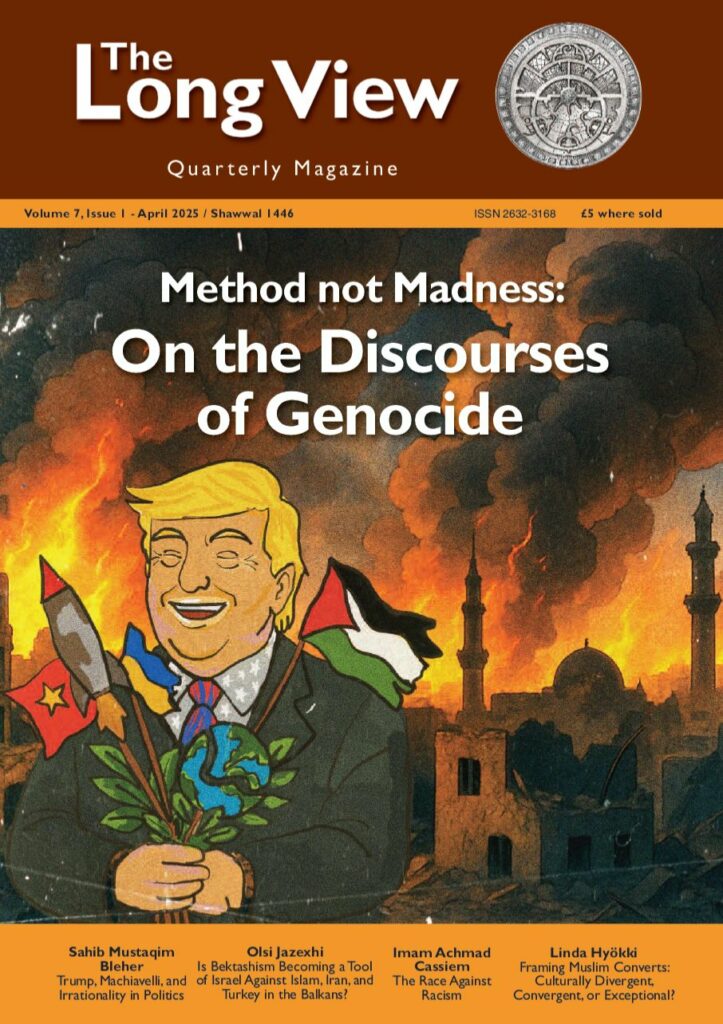

Method not Madness: On the Discourses of Genocide

Volume 7 – Issue 1 – April 2025 / Shawwal 1445

Editorial

The idea that Donald Trump is an out of control political oddball has become a commonplace of media presentation. Ever since his re-election to the Oval Office, the erstwhile celebrity businessman has hogged the political spotlight by disrupting the global economic order via a regime of tariffs against trading partners and turning on its head US foreign policy vis a vis Ukraine. Proudly pursuing a populist nativism, the US president has revelled in throwing into disarray his country’s enduring relationships with friends and foes alike. This has given rise to a narrative of the fearless gun-slinging American cowboy who will let nothing stand in his way to achieve and maintain political hegemony.

However, according to Sahib Mustaqim Bleher, the author of the first piece in this edition, not all is as chaotic as it would seem. Behind the headlines there is a method to the apparent madness, informed by Machiavellian ruthlessness and unscrupulousness, that seeks to restore flagging US global supremacy. Having realised that it cannot defeat Russia in the proxy war over Ukraine, Washington has sacrificed Kiev to focus its attention on West Asia, where the Hamas breakout from Gaza in October 2023 ran a coach and horses through decades of US policy and the assumption that Zionism had triumphed and the Palestinians had finally been defeated.

Framing US policy in terms of a neo-colonial enterprise fused with Zionist supremacism, Bleher sees the “Hamas jailbreak” as a defining moment in global politics, one in which the US has lost control and in which its reaction is being dictated by external forces.

In fact, the resistance has hurt the US/Zionist alliance so much that it has decided that soft power is no longer sufficient to subdue the Palestinians and only military might can defeat them. Cue the genocide and the oft-stated intention of ethnically cleansing the native inhabitants to complete what the axis failed to achieve pre 1948 and in 1967. This is indeed their final solution.

The ongoing Israeli genocide has lifted the mask on many things but few more revealing than the cooperation and complicity of Muslim nations and actors. A lesser known aspect of this is the support that the current government in the tiny Balkan state of Albania is providing to the Zionist state. A majority Muslim nation, Albania is ruled by a regime that has co-opted the heterodox Sufi order into the country’s polity, with the Prime Minister Edi Rama going as far as declaring at the UN on September 23, 2024, the creation of a sovereign Bektashi state in Tirana along the lines of the Vatican. This has coincided with a much longer love-in for Israel and a consequent severing of diplomatic relations with Iran alongside a wider attack on traditional Sunni and Shia Islam.

Olsi Jazexhi questions whether Bektashism, is being weaponised by the state to advance US and Israeli interests, key among which is to sow division among Muslim states. Certainly the evidence points in that direction. Albania hosts a base for the anti-Iranian revolution MEK opposition group. In September 2024, when Israeli President Isaac Herzog visited Albania, he reportedly had a special meeting with the self-proclaimed World Leader of the Bektashis, Baba Edmond Brahimaj (Baba Mondi). On October 4, 2023, Munr Kazmir, Vice President of the American Jewish Congress, visited the Continental Hospital owned by the Bektashi World Headquarters. On October 7, 2023, when Hamas attacked Israel, Baba Mondi sent a message to the Israeli embassy condemning Hamas and expressing support for Israel. Throughout the 18 months that Israel has committed genocide in Gaza, the Bektashi World Headquarters has not once condemned Israel.

The alliance between Albania and Zionism, arguably the most violent expression of white supremacism, is perhaps not as unlikely as it appears. Emerging as a reaction to Ottoman domination, Albanian nationalism has always been imbued with a racial separatism that seeks to identify with western Europe, even if Europe is reluctant to reciprocate. Viewed through this lens the newfound affinity of the ruling regime with Israel may be ideological as well as opportunistic. It is ironic that in seeking to identify with a West that it sees as civilisationally superior, Albania finds itself sharing a bed with the most barbaric regimes on earth, regimes that are still wedded to notions of white supremacism.

The third essay in this issue is by the late great South African imam and civil rights activist, Achmad Cassiem. It unpacks the concept of Zionism as racism through an Islamic cognitive frame. Although it was written 25 years ago, the analysis is even more relevant in an age where we see Israel, the embodiment of Zionism, trying to exterminate a whole people on the basis that they are an obstacle to the realisation of a racist philosophy. Drawing on his experience and involvement in the struggle against apartheid in South Africa, Imam Cassiem draws parallels with the Zionist movement while also identifying the differences. He concludes that “anti-racism is the only genuine, authentic, potent and revolutionary antidote for the poison of racism.” Racism and anti-racism cannot co-exist. “We have to combat racism and racialism in all their forms. From an Islamic point of view this is not the point of being tolerant but the point of principle.”

Our final essay departs from the tragedy in Palestine to look at, amongst other things, how racism is impacting the growth of Islam in Finland. Increasingly, academics across Europe are seeing Islam as not purely a function of migratory processes, often themselves occasioned by geopolitics, but also an indigenous phenomenon owing to the rising number of conversions. Homing in on her native Finland where Muslims constitute approximately 2.3% of the total population, Linda Hyokki identifies the challenges and opportunities associated with a burgeoning convert community. Converts can serve as a cultural bridge between “foreign” Muslims and “native” non-Muslims but nevertheless often suffer the same exclusionary dynamics as Muslims from migrant backgrounds. They can also, deliberately or inadvertently, instrumentalise their cultural proximity to mark themselves as more authentic and therefore more acceptable to in a society where Islam is still largely portrayed as hostile and alien, thereby exacerbating Islamophobia and racism.

The bridges that need to be built between oppressed people require conversation, understanding, respect for differences, and above all a focus on the main narratives and infrastructure of oppression that we are all subjected to. Let’s keep those conversations going.