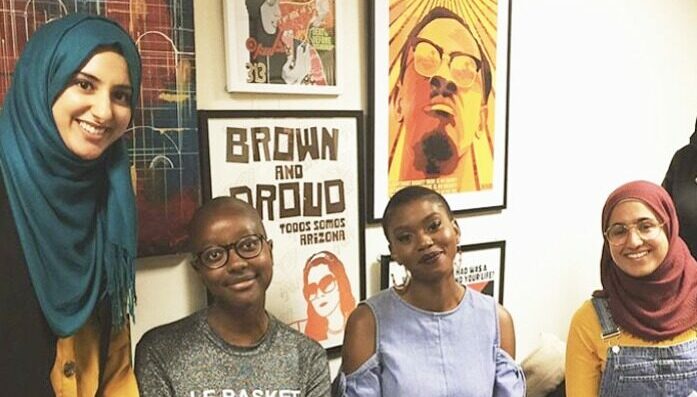

Last month, we were joined by Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan, Waithera Sebatindira and Lola Olufemi to discuss their book A FLY Girl’s Guide to University: Being a Woman of Colour at Cambridge and Other Institutions of Elitism and Power. Chaired by Narjis Khan, who also graduated from the University of Cambridge in 2011 with a degree in Social and Political Sciences, the women had an amazing discussion on various subtopics surrounding anti-racism activism.

Watch the full conversation here and below. A full report follows under the video.

All three authors began with reading an excerpt of their writings from the book. Narjis opened the conversation with asking about FLY: – how was FLY born, how did the idea of the book come from it and how did you all connect?

Lola Olufemi (studied English at Cambridge University and has completed a Masters in Gender Studies at SOAS) said FLY started in 2012 by a group of black women in Cambridge, including Priscilla Mensah who was a key person in the formation of FLY. Lola described FLY as a social space for black women to talk about experiences, and it grew as a space, with more people getting involved and it grew to be more politicised with a clear feminist ethos. It is a social space to watch films, attend plays, provide support and solidarity, hold themed forums, and get together to talk about issues. It grew into a space for women of colour and then non-binary people, and it became known as a space that conserved activist energy and politicised people. For Lola, it gave her especially a space to articulate feelings and make friends.

Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan (studied History at the University of Cambridge and has completed a Masters in Postcolonial Studies at SOAS) said that even if FLY started out as a social space, it inherently political; “we were women of colour meeting together in that institution, we wee seeing our experiences from our vantage point”.

Waithera Sebatindira (studied Law and Gender Studies at the University of Cambridge) said: “FLY is almost like a training ground if you have no experience in organising, it’s a very effective and safe space”.

Narjis mentioned that microaggressions came up in the excerpt that Waithera read: “microaggressions explained those interactions that racially profiled, stereotyped, patronised, excluded, otherised, dehumanised and tokenised me in different ways. At last I had a word to describe daily experiences.”

Suhaiymah explained that there is something really powerful about naming things that did not have a name before, “we have all experienced microaggressions and having a word to describe that thing, makes that thing less natural and when you can see that something isn’t natural, you can understand if it was constructed or formed or that there’s something behind it.” On wearing hijab, Suhaiymah said people would ask her what she thought of Palestine or Charlie Hebdo, and why do you want to kill people because of Allah. She would also receive the inverse where her hijab was exoticised, with people commenting “Oh, this hijab is so beautiful”. Suhaiymah went on to explain that it depends on where they are coming from. “Most people in Cambridge have never met a person of colour before, most have only been educated in white private schools. But when it [microaggressions] comes from your academic supervisors and tutors it is really violent. One of supervisors said to me “if you want to improve your essays, you need to write like one of boys from Eton, like the ones that you don’t like!” What they are saying is that the entire way I have been raised and socialised is the reason why I cannot write a good essay.”

Lola discussed that a realisation that comes later with microaggressions is to question what it means then to want to belong to an elite institution or what does it mean to want other people to recognise that actually you could go to Cambridge. It “means we’re ascribing to Cambridge a prestige of power, an authority that it shouldn’t really have because we have a deeply hierarchical education system. There were also ways microaggressions enabled me to figure who I wanted to be allied with – I realised I didn’t want to belong with these people, that was something very formative.”

Lola told the audience about a friend who handed in her first essay and her supervisor asked if English was her first language – Lola said, “that was underpinned by a whole set of assumptions about language and the assumption that she could not have been raised in this country. Or that the way that she was constructing her sentences was so alien that it didn’t belong within the institution as it had been demarcated. In terms of how we shared with each other, starting with the microaggressions was a really important step for people who had never thought critically about race or gender, and took these things to be natural. We’d come together and people would tell stories, started as anecdotes, as facilitators we then took it a step further [by asking] can we see how this might be racist, sexist or these two combined?”

Narjis asked, “what does Odelia Younge mean when she says white comfort often leads to black isolation in institutions of power and racism?”

Lola said she felt that in places like Cambridge, they operate on coalitions so that there are ways people have social interactions or they make social pacts that include and exclude other people. It is seen in clubs, in groups, in the old boys’ networks, in a kind of underground way that a lot of these systems of privilege operate. “If you are on the periphery of that, you are exactly that – you are isolated and alone and you are not granted access to those things. The point is not that you want access to those things, the point is that those things shouldn’t exist. You want the abolition of those things.”

“I lost a lot of friends in that first year [of university] because I was writing and saying all these things… I felt the power of that isolation of being frozen out of experiencing more microaggressions because I was organising and using language that made other people feel uncomfortable, and named the things that were happening to me. It was FLY that taught me that and the isolation can be a strength because when you come and organise together, you are not actually isolated. What you have is a deeper understanding of yourself and others, which makes the space bearable.”

Suhaiymah commented on the point of comfort, saying “something that took me a long time to realise was that for all of my first year [of university] I was trying to make other people uncomfortable – I would have thought I was trying to make myself comfortable, and so therefore I would not say ‘I have to go to pray’, I would say ‘I’ll be back in a second’. What struck me was that as much as I was doing that, of course when everybody saw me, they were not seeing a random white person, they saw exactly what I was. So when I realised that this whole thing was built on the false understanding that on some level I can trick people into thinking that I am like them, that really changed things for me. I realised there was nothing to lose in actually then living my truth. In doing that, people were much more able to have conversations that they wanted to have with me and I was more able to too.

Look at the new government, someone like Sajid Javid – this idea that if you make yourself palatable and make the white people around you comfortable, you will be given humanity. But at the end of the day, he was not invited when Donald trump came to the parliament and he wasn’t invited to the dinner – just proves that as much as you can try to be the ‘good one’, you’re not going to be.

I found that very liberating, especially in the sense of ‘good Muslim’ versus ‘bad Muslim’ – how many times can you condemn terrorism? How many times can you say you think forced marriages are bad, FGM is bad? – or whatever the thing is…

The best Muslim, the one that would be really palatable and really good, is just not a Muslim.”

Waithera explained what anti-racism means: “if you think about what radical anti-racism politics is, it’s targeting whiteness. Anti-racism isn’t just about not wanting white people to be mean or dominate other people. But it is about understanding what whiteness is and why it is. That for me was useful in terms of power structures and to discover how deeply ideological racism is. I find that a succinct way of getting to the root of it being that we are not just targeting oppression that happens to be racist, we are targeting a very specific ideology that has constructed whiteness and is doing all of these other things to uplift it.”

Narjis asked, “how do you engage with those sorts of people [i.e. people of colour who align themselves with white supremacist structures and logic]?”

Lola talked about the new government cabinet, saying representation isn’t the be-all and end-all. “We got wider representation for state violence. As people who do not align themselves with that ideology and align themselves with liberation politics, to clearly demarcate those people as your enemies as well, there’s no amount of logical argumentation that could convince Priti Patel that she is an Asian… [Representation] is a way of shielding that because the discourse then becomes ‘look at how great Boris Johnson is, he loves people of colour’ – and not actually that these people are very ideologically dangerous, and now they are so embedded within the state apparatus that they have power to enact the most violent policies. For example, Priti Patel just said she wants to do a mass overhaul of the immigration system – that’s most important. It realigns our focus on whose lives are at stake, how their ascension puts other people in danger.”

Narjis’ final question was on mental health and perseverance: “Even though small acts of resistance can be exhausting and can affect your mental health, what advice do you have for people who do want to persevere, who do want to engage in those small acts of resistance but at the same time might feel like they need to take a step back for their own sanity, health and survival?”

Lola said that the idea of protecting your sanity and mental health is crucial to the success of any organising project. She said “we obviously live in a very neo-liberal society that purposefully isolates us from one another and so the tendency is to say ‘I need to recuperate’ and ‘I need to protect myself from these things’ and often what ends up happening is isolation, when actually what’s at the core of any liberatory project is relation, the ways that we relate, look after and care for each other. Self-care has been drained of its meaning by white liberal feminism, but togetherness – like cooking for someone, checking up on them, looking after their baby – are ways we signal to one another that we care about each other and that care is at the centre of the new world we want to build.

My advice would be it is an absolutely okay thing to take a step back from projects and things going on because this life is long, and we want to live. I don’t think we can underestimate the way the world kills us. Anybody who has had to cross borders, anybody who has family abroad, knows that the move and adjustment to this country cuts peoples lives short. The racial disparities and the ways that we die in comparison to our white peers and white counterparts is very serious. The way we overcome that is through community – which has always been at our centre.”

Waithera urged for the need to reframe the way we think about self-care, “If we go back to that quote by Audre lorde, self-care is an act of political warfare and it is as radical as all the organising work that you’re doing. It is absolutely as necessary. And I don’t think of it as taking a step back, rather it is taking a step forward; it’s all part of the work we’re doing, looking after ourselves, and not just because it is necessary but because we are not supposed to be able to, because the state and structures of oppression try to constantly strip us off that ability to try and receive that care. It is as important as all the other work we do in this context.”

Suhaiymah ended the conversation before the Q&A with making mention of a hadith the Prophet (pbuh) said ‘love for your brother what you love for yourself’. Suhaiymah said “if you want to do that you actually first have to love yourself, you have to love something for yourself and if you don’t actually give yourself the respect and care that you deserve then your politics towards everybody is going to be rubbish, the way that you can care and treat everyone will be undermined.”