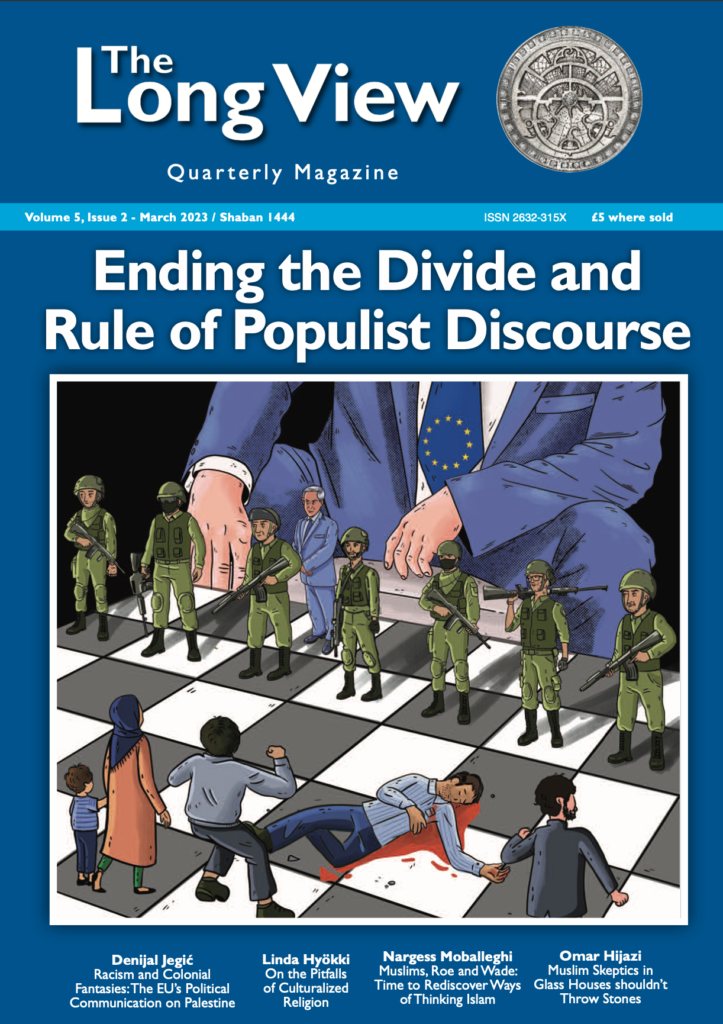

Ending the Divide and Rule of Populist Discourse

Volume 5 – Issue 2 – March 2023 / Shaban 1444

Editorial

Not a day goes by – in the so-called West at least – where moral and social panics and hysteria rage. Many, but not all of these involve Muslims and Islam in some way or form: the great replacement theory, the idea of Muslims as entryists and fifth columnists, or the capitulation of Western legal systems to sharia law, the political and military resistance to Israeli occupation of Palestine. Others however do not – on the surface at least – have a Muslim focus: the fight over gender and identity, the teaching in schools of non-heterosexual lifestyles as normative, male and female roles in society, and the fight over the limits and even the legitimacy of abortion. Whether cultural, religious, political, these panics are often portrayed in the populist imagination as existential questions, demanding resolution if not by the state, then by the mob.

As Islam is a way of life, it is unsurprising and indeed apt for Muslims to have opinions on any and all debates. Many times, this takes the form of supporting one or other side in a debate and arguing that Islamic values align with that side (on occasion Muslims can be found using this tactic on both sides of a debate). Whilst there can be merit in these methods, doing so without an overview of the issues being discussed can reduce such attempts to simply reproducing the argument of others with no Islamic insight or input.

This issue picks apart some of the problems arising out of such interventions and debates. Our lead piece, provides a powerful critique of how the racism of western, specifically European Union rhetoric on Palestine, is not only ubiquitous but foundational. Not only is there is no engagement to be had with this type of discourse, its premises mean that to challenge it, those in opposition – Muslim or otherwise – must take a decolonial overview before tackling it.

In this essay, Denijal Jegić takes a cold, hard look at the positioning of the European Union’s position on Palestine. It is not simply a case of hypocrisy that EU institutional language is racist but as Jegić argues, central to the idea of Europe itself, as shown in hideous candour in the recent statements of Josep Borrell. The Union’s High Representative for Security and Foreign Affairs claimed in effect, that the non-European world was a jungle, always threatening to overgrow the European garden. The communiques of the EU on Palestine simply reflect the approbation of a colonial project for continuing settler colonial and indeed genocidal activities in Palestine by Israeli forces.

Without this type of political and moral overview, conversations about Palestine can and are lost in a frame of reference that erases colonial and genocidal violence and creates a debate, at best about competing sets of rights (Israeli versus Palestinian), or worse about the legitimacy of colonial settler projects.

Looking at the experiences of Muslims in Finland, both converts and those raised in the faith, Linda Hyökki argues for a Muslim language and praxis that challenges prevailing discourse around minorities and cultural rights. Specifically, she argues that analogising Islamic practices, whether fasting, praying or celebrating Eid with Christian practices for the sake of intercultural communication and also legal recognition creates many pitfalls. Not least of these is the reinforcing of the perception of majority society as culturally Christian (even when in many cases the majority of many Europeanised states practice the faith less), therefore giving grist to the mill that there is a culture war or clash between the faiths. Worse still, is the fact that in turning Islamic faith practice into cultural rights as per the prevailing discourse, we risk the same loss of the same faith practice as per the majority society – in effect Muslims secularise, identifying with Islam in a nominal way.

Nargess Moballeghi looks at the furore after the overturn of Roe v. Wade by the US Supreme Court last year. The fallout from this case saw people from all walks of life, worldview, faith and geography argue over which side was right. As Moballeghi points out, neither of the pro-life or women’s bodily autonomy positions sit within in any frame of Islamic thinking, yet Muslims were to be found in both camps arguing vigorously that the side they had taken was the Islamic one. Moballeghi argues that a moment for changing the terms of the conversation has been lost.

Our final contribution is from Omar Hijazi who looks at the self-imposed limitations that even those arguing for a transformative Islamic world-view place on themselves. In response to a piece from a well-known blog, attacking Iran’s Islamic revolution, Hijazi argues that this type of critique is simply a mirror of secular westernised polemic given an ‘Islamic’ legitimacy using a sectarianised lens. Hijazi argues that whilst critique is necessary and vital of all movements, especially Islamic ones, the type espoused in the blog he takes issue with lacks any depth, and finds the author(s) who claim to be also the deepest critics of western politics and mores in fact in bed with the very same.

Whilst Muslim ways of thinking are the focus of three of these essays, the issues raised are pertinent to all of us who want a world transformed from the current inequalities and violence of our age. What hope do movements and projects for transformation have when we are unable to get beyond the limitations imposed upon us by the very powers and systems that oppress us? It’s time to change the conversation.